Author: Atul Kapur / Codes: / Published: 12/09/2018

Warning

The content you’re about to read or listen to is at least two years old, which means evidence and guidelines may have changed since it was originally published. This content item won’t be edited but there will be a newer version published if warranted. Check the new publications and curriculum map for updates

It’s safe to say you will likely see a few of these, as minor injuries are a very common occurrence in childhood with around 20-30% of all paediatric attendances to the Emergency Department involving minor injuries or trauma.

The vast majority of injuries are accidental. In the UK many households involve a single parent looking after multiple children of different ages. Some younger children may have a short period of time where they are not properly supervised and boom! Something happens. They fall, hit their head, break their wrist or burn themselves with a cup of tea. Accidents do happen.

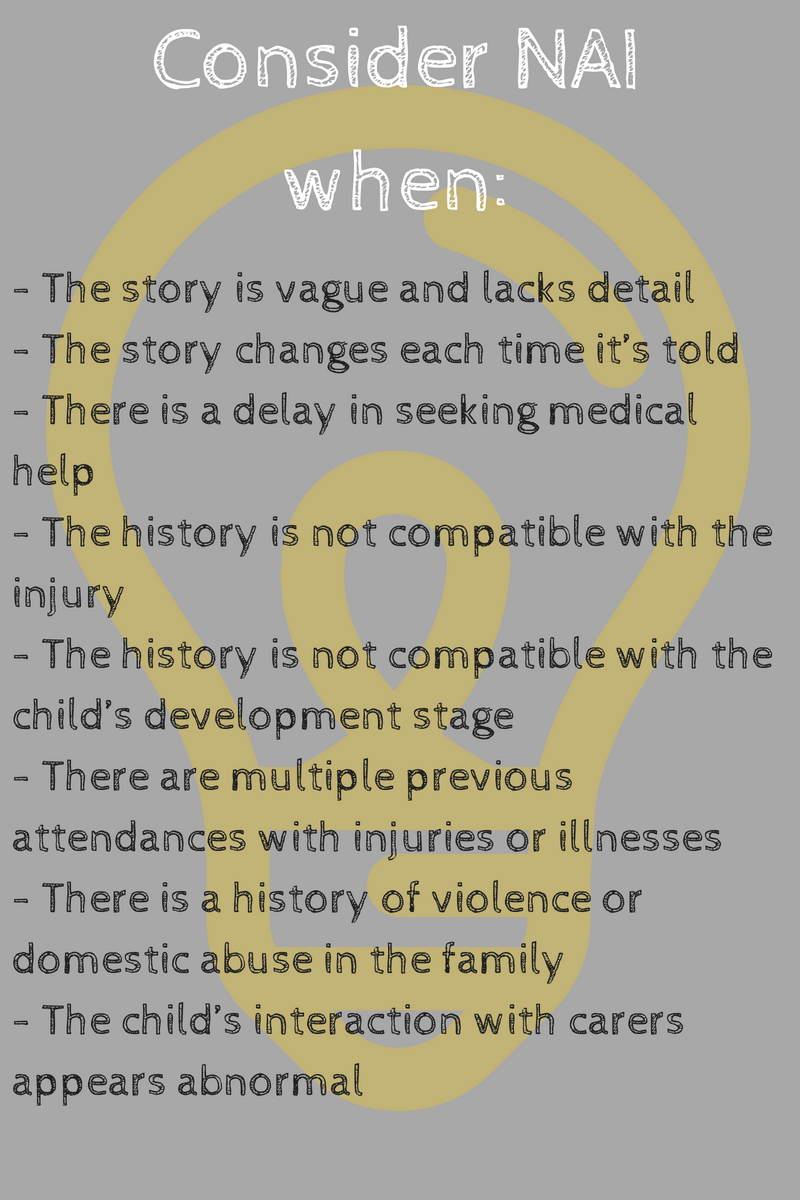

Saying that, think of non-accidental injury (NAI) as a differential diagnosis in all children presenting to ED with minor injuries. Do not ask every parent whether they did something to intentionally cause harm, but think of it in the back of your head. Always ask yourself if there is some part of this story that doesn’t fit. If in doubt speak to a senior physician about it.

Analgesia

Assess the pain score and give analgesia appropriately. Useful pain assessment scores (like the Wong-Baker Faces) involve visual representation of the child’s pain.

Analgesia examples according to pain are:

For mild (1-3) pain oral/rectal paracetamol and/or oral ibuprofen should be adequate

For moderate (4-6) pain you may add oral morphine (Oramorph) if a combination of the above is not enough

For severe (7-10) pain you may need to use Entonox as an interim measure before getting in some stronger analgesia. Intranasal Diamorphine is great for severe pain and is commonly used, it has a rapid (2-5 minutes) mode of action and gives you 30-60 minutes of analgesia, giving you time for other measures like splints and plaster. It also has an anxiolytic effect which will help if you need IV access. IV morphine may also be suitable for severe pain.

You will find that every department has a typical analgesia ladder according to pain score so do as the nurses what is usually used for patients according to how much pain they are in. Also remember that children’s pain is exacerbated by fear, so use distraction techniques and get someone (play specialists especially) to help you.

Wounds

Clean all wounds thoroughly before deciding how to repair them. If this is new to you, ask someone to show you how. Make sure there are no small foreign bodies. Xrays may be needed to exclude this but specifically mention on your request that you are excluding foreign body.

See if the wound edges come together. You can then use adhesive strips, tissue glue, or sutures to close. Get advice from a senior nurse or doctor to help you choose the right method.

Wounds in areas like the face, lips, forehead, neck or hands may need closure from specialist plastics or maxillofacial services as scars in these areas can obviously have significant cosmetic consequences. Ask a senior if unsure. Many departments have local anaesthetic gel which can be applied to the wound for analgesia.

Wounds of the internal mucosa of the lips and wounds of the tongue heal very well and quickly (in just a few days) without any intervention. Just remind parents to make sure food does not get stuck in these wounds until they heal.

Always remember to consider tetanus risk with any wounds and document the child’s vaccination status.

Fractures and x–rays

Children’s bones are quite soft/less brittle than those of adults and incomplete fractures occur (like torus or greenstick fractures), and the growth plate is commonly involved. We tend to have a lower threshold to xray limbs to look for fractures. Consider that even if the Xray is normal, but the child is clinically symptomatic, there may still be an injury to the bone. In this case the safest thing to do is to immobilise the limb and reassess either in a review clinic in a week or even in fracture clinic. Xrays of the axial skeleton such as thoracic or lumbar spine expose children to a large amount of radiation so if considering these xrays get senior input. Interpreting Xrays in children is difficult takes practice so routinely get a senior or nurse practitioner to cast their eye on it.

Upper Limb injuries

Remember your CRITOE!

Clavicle Heal spontaneously very well, apply a broad arm sling and refer to your local guidelines for followup (many places will discharge without followup if appropriate criteria are met). The main worry is when the overlying skin is compromised from tenting or if there is neuromuscular compromise.

Supracondylar humeral fracture Common, peak age around 7 years, examine and document neurovascular status carefully. To detect subtle fractures in a true lateral elbow xray draw a line along the anterior humerus, this line should intersect the middle third of the capitellum, if not it’s a fracture. Remember to also look for your anterior and posterior fat pad signs.

Radial head fracture may not be visible on xray, look for raised anterior or posterior fat pads on the xray which indicate joint effusion.

Pulled elbow Common in ages 1-3 years, usually present with a clear history of pulling the arm by the hand and feeling a click. Requires a simple manipulation to fix and the child should be back using their arm normally in 10-20 minutes. Does not require an xray.

Radius/ulna fracture I call this the trampoline injury, check neurovascular status, if severely angulated or displaced refer to orthopaedics.

Distal radius fractures The most common fracture in all ages in children. Can be very subtle on xray, commonly are “buckle” fractures. Refer to orthopaedics if severe displacement or angulation. However, most of these will heal well, a futura splint is usually all that’s required for immobilisation.

Lower limbs injuries

Knee injury Xray if non-weight bearing, large effusion or significant mechanism. The “Ottawa knee rules” can be applied from puberty. Check for ligament laxity, anterior/posterior cruciate ligaments, and medial/lateral collateral ligament. Also check extensor mechanism by using the straight leg raise test. If any of these are abnormal discuss with orthopaedics or a senior.

Patellar disclocation Due a direct blow or twisting of the knee. Generally very painful and distressing for children and parents. It will be clinically obvious so xrays are not needed pre- reduction. Give strong analgesia as well as Entonox and reduce by applying pressure to the lateral aspect while extending the knee. Xray post reduction, apply a cricket pad splint and refer to fracture clinic.

Toddler’s fracture Common, ages 1-3 years, spiral tibial fracture. Due to direct blow or twisting. May be subtle clinically and on xray. More of a clinical diagnosis so if the xray is normal and the child is tender over the tibia, treat it as a fracture, immobilise in plaster and refer to fracture clinic.

The child with an atraumatic limp requires another blog altogether and PEMplaybook has this covered in their post here.