Author: Meriel Tolhurst-Cleaver / Questions & update: Woei Jiun Yap / Codes: / Published: 08/05/2017

Peer review: Naomi Simmons

It’s a common card to pick up in some paeds EDs – the yellow newborn. But whilst this can be an ‘easy’ one, such tiny babies can strike fear into the hearts of some! So, a quick review of what to look for, and what not to miss, should keep us all calm when presented with a baby who looks like they could be auditioning for the Simpsons.

When thinking about neonatal jaundice we can break it down into early (generally regarded as up to 14 days) and prolonged (over 2 weeks in term babies, or over 21 days in preterm infants). This post will look specifically at early jaundice.

Most babies presenting to the ED with this complaint will be a few days old. It is rare for us to see it in the first 24 hours of life, as many babies are still on postnatal wards at this time. But of course, some babies have an early discharge from hospital (which can be as little as 6 hours after a normal vaginal delivery ouch!), and some are born at home, so it is possible for them to pitch up to the ED.

Jaundice in the first 24 hours of life

Jaundice in the first 24 hours of life is ALWAYS PATHOLOGICAL and should be treated very seriously.

When you see it, think of sepsis, ABO/rhesus incompatibility or haemorrhage (e.g. subgaleal bleed). These babies should be seen and investigated quickly, with a septic screen, FBC, Direct Coombs test and split bilirubin level, and referred promptly to the General Paediatric take for admission and management.

Assuming the jaundice isn’t in the first 24 hours of life though we can be a little more discerning with what we do, depending on our history and examination findings.

Early Jaundice after the first 24 hours of life

So how do these babies present? Well they are usually a few days old (commonly 2-6, but may be earlier or later), and come with a history of increasing, or newly noted jaundice. They may have been asked to attend by a midwife or GP.

In some areas of the UK, babies may bypass the ED and be admitted directly to a ward, as community midwives send blood samples in from home and only refer the patient if they need treatment. Aside from jaundice, these babies may also have features such as lethargy (not waking for feeds), poor feeding (not interested in, or falling asleep whilst feeding), and they may be floppy or irritable.

So how should you approach these patients? Start by congratulating the parents on the birth of their baby, and recognise and acknowledge the fact that they are probably exhausted and anxious. Take a thorough history, including birth history, gestation, birth weight, risk factors for sepsis (although don’t let this falsely reassure you as many babies with early sepsis don’t have ‘risk factors’), date and time of birth (you’ll need it to plot the bilirubin later), history of bruising (e.g. forceps delivery), method and amounts of feeding, and mum’s blood group. Examine the baby from top to toe, noting whether the conjunctiva are icteric and how far down the body the jaundice is evident (it starts on the face and progresses downwards). Look for features of sepsis such as irritability, floppiness, poor perfusion or a raised or tense fontanelle. Don’t forget to carefully listen to the heart and check the femorals (just in case you are the first to also pick up congenital heart disease). Weigh the baby (totally naked, yes you have to risk getting weed on) and calculate how much weight has been lost from the birth weight. Every hospital has a different guideline, but generally speaking if it is about 10-12% you’ll need to discuss the baby with the paediatric team. Even if their jaundice does not need treatment these babies are often admitted for observation of feeds.

If there are no red flags for sepsis in the history, and the baby examines well but has significant jaundice (i.e. you can see they are jaundiced) then NICE recommends you send a split bilirubin, haematocrit (FBC), group and Direct Antiglobuin Test (DAT, aka Direct Coomb’s Test or DCT). All of these can be done with a heel prick. Also remember to consider adding a G6PD if the baby is of appropriate ethnic origin. If there is poor feeding, it’s probably sensible to also include a U&E (as hypernatraemic dehydration is common), and a blood sugar.

Any concerns for sepsis and you need to have a have low threshold for doing a full septic screen (blood, urine and CSF cultures) and commencing appropriate IV antibiotics. If in doubt, you can get advice from the paediatric team. Remember that newborns can have very vague features of sepsis and may not mount a fever or much of an inflammatory response on their bloods. Be concerned if anything is amiss with their feeding, sleeping, general handling or appearance.

NICE has updated their guideline and it recommends the use of a bilirubinometer in the first instance rather than blood tests, if one is available. This is not accurate for babies <24 hours so it should not be used in that instance. This is great for use on the postnatal wards where they are doing hundreds of bili checks, but most EDs might not have one of these, as we have relatively fewer cases. So a heelprick it is! If you do have access to a bilirubinometer device then check out the NICE guidance for when to use it and when it is contra-indicated. This video shows how to use one.

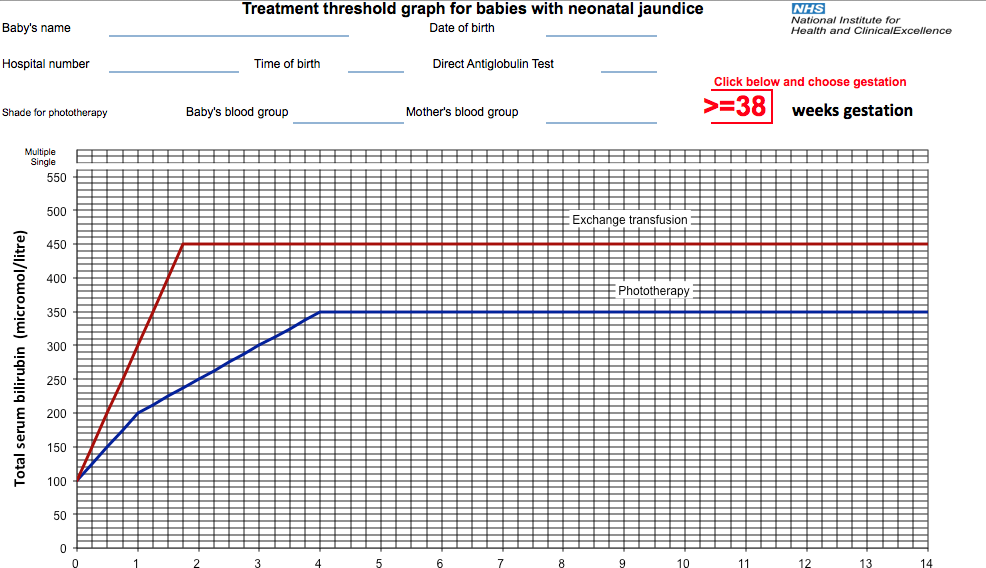

Get the bloods done early and be warned that they clot very easily, largely because newborn babies have such a high haematocit, but potential poor feeding and poor perfusion also doesn’t help. If possible, get someone experienced to do the heel prick. Once the bloods are back you need to download a gestation specific bilirubin chart and plot the bilirubin at the appropriate time from birth (this is when you need an accurate time and date of birth from the parents).

Remember that each little box on the chart is equivalent to 6 hours. If the bilirubin is above the treatment line, the baby needs admission for phototherapy, so refer to the General Paediatric take. If they are over the exchange transfusion line, they are at risk of kernicterus, seizures and coma. They need urgent phototherapy with as many light units as possible and IV fluids whilst an exchange transfusion is organised (this takes time), but get help early in view of this.

If the bilirubin is below the line then the family get to go home -hurray! But bear in mind that if it is less than 50 micromol/l below the line you’ll need to organise for a further blood test within 18-24 hours (18 hours if there are recognised risk factors, which include sibling requiring phototherapy and exclusive breastfeeding). The NICE guidance has more information on this but also ask around locally as to whether the baby will have to return to ED or whether a community midwife could send a sample in.

A quick reminder about performing ‘split’ (sometimes called neonatal) bilirubin samples. The result will show the conjugated fraction, the unconjugated fraction and the total bilirubin level. A conjugated hyperbilirubinemia, where the conjugated fraction is 20% of the total level is normally detected on a prolonged jaundiced screen (performed after 14 days). It is ALWAYS pathological, and normally represents hepatobiliary disease, such as biliary atresia. So you should always just check that the conjugated fraction is <20% of the total and if not the baby would need admitting under the paediatric team. This link has more information about conjugated hyperbilrubinaemia and the contact details for the UK Liver Units in case you need more help.

Causes of Jaundice

What causes the jaundice in these babies? Well, the ‘first day’ list above is still relevant in the babies over 24 hours of age (so sepsis, ABO/rhesus incompatibility and haemorrhage should still be in the back of your mind). I personally use a conscious forcing strategy to mentally exclude sepsis whenever I see a jaundiced baby. There is more information about strategies such as this, and other ways to unbias yourself in this excellent podcast from Emergency Medicine Cases.

Other causes include: haemolysis, which should be picked up by your DAT or blood film; bruising or bleeding, which should be evident on examination; G6PD- test for this if you have any concerns; or congenital infections, which again should be evident on examination. Most babies however, will have physiologic jaundice or breast-milk jaundice. Whilst these are both diagnoses of exclusion, given the high incidence of jaundice in the newborn, NICE doesn’t recommend doing more investigations than those listed above at first presentation. If the jaundice is prolonged that is when you start to pull out the stops but you can read all about the investigation and management of prolonged jaundice soon in a follow-up blog on this site.

References/further reading: