Authors: David Patrick Ross,Scott Dickson, Kelly Kwok, Isla Waterson, Luke Zhu / Editors: Donogh Maguire, Ewan Forrest / Reviewer: Beth Newstead, Raghaventhar Manikandan / Codes: / Published: 09/11/2018

Alcohol use disorder (AUD) is defined by the World Health Organisation as consuming more than 40mg/day of alcohol for males and 30mg/day of alcohol for females. It is estimated that one in six adults in Europe has AUD.1 A study performed in a UK ED found that around 20 percent of attendances to the department were linked to alcohol and that around one third of these patients would subsequently require admission to hospital.2 In Scotland alone this translated to 32000 alcohol related hospital admissions in 2022/233 representing a significant burden the health service.

It is estimated that between 8-11% of patients with AUD who are admitted to hospital will go on to subsequently develop alcohol withdrawal syndrome (AWS).4,5

AWS occurs as a spectrum of disease defined by DSM-5 as two or more of6:

- Insomnia

- Autonomic dysfunction (tachycardia and sweating)

- Tremor

- Nausea and vomiting

- Agitation

- Anxiety

- Seizures (generalised)

- Hallucinations

Symptoms can develop after anything from several hours to a few days following cessation of alcohol intake.

Symptoms can range to mild tremor and anxiety through to Delirium Tremens (DT). DT represents the most severe form of AWS where patients develop a severe agitated delirium with hallucination.7

Pitfall

Be careful with your terminology. All patients who have Delirium tremens have Alcohol Withdrawal Syndrome but not all patients with Alcohol Withdrawal Syndrome have Delirium Tremens.

Pitfall

Beware alcoholic hallucinosis- this rare condition occurs in chronic heavy drinkers and patients typically present with clear cognition but who complain of persecutory hallucinations which are often auditory.8 This could be potentially confused with alcohol withdrawal.

Pathophysiology 1

AWS develops due to an imbalance in neurotransmitters in patients brains caused by chronic consumption of alcohol or to give it its proper name ethanol.

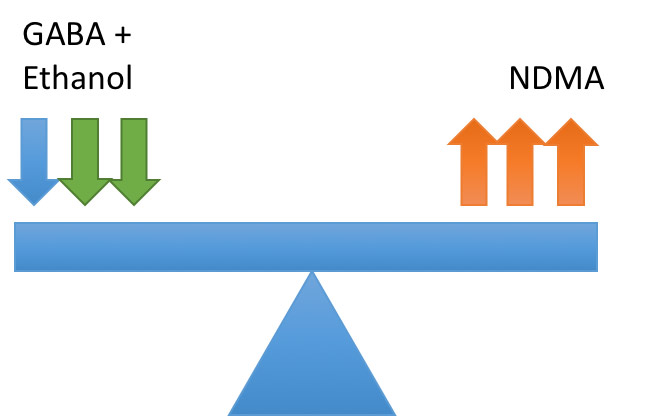

The two key neurotransmitters involved are GABA which in inhibitory and NDMA which is excitatory. In health these are balanced as shown below:

Pathophysiology 2

Ethanol acts on GABA receptors potentiating their inhibitory effects. To maintain homeostasis the neurones down regulate GABA and upregulate NDMA:

Pathophysiology 3

On cessation of drinking ethanol is removed causing imbalance in the neurotransmitters leading to hyper-excitability:

This hyper-excitability leads to the clinical syndrome known as alcohol withdrawal syndrome. It is worth noting that only a drop in ethanol levels is required to cause this imbalance so patients can still show symptoms of withdrawal despite still having a detectable blood alcohol level.9

Screening for AUD

The key to minimising the impact of AWS on the patient is early identification of the fact that the patient is at risk. NICE10 and the RCEM11 suggests that patients should be screened for AUD using questionnaire style assessment tools such as the Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (AUDIT) or Fast Alcohol Assessment Tool (FAST).

Focused Alcohol Screening Tool (FAST)

These screening tools only identify AUD and do not predict likelihood or severity of AWS. Several screening tools have been developed which attempt to quantify risk of AWS12-16 though none of these is in current widespread use. The Glasgow Modified Alcohol Withdrawal Scale (GMAWS) protocol classifies patients with AUD plus at least one of the following as high risk of complicated AWS.17

- High FAST score (>12) at presentation

- Previous severe withdrawal or alcohol related seizure

- Severe symptoms of AWS at presentation

Requirement for Admission

NICEs guidance on alcohol use disorder states that patients:

- Presenting with or at risk of DT

- Presenting with or at risk of seizure

- Are frail, vulnerable or have multiple co morbidities

Should be admitted for medically assisted withdrawal.10

Obviously some patients will require admission as they have presented with another issue/condition.

Pitfall

If discharging a patient with mild AWS not felt to require admission make sure NEVER to advise them to suddenly stop or reduce their drinking as this could precipitate severe symptoms. NICE recommend instead that they should be signposted to outpatient services where controlled withdrawal can be organised.10

Patients presenting with AWS should be assessed using an A-E approach. It is important to ensure they do not have a serious underlying pathology which has precipitated them stopping or reducing their alcohol intake. Basic blood tests, ECG and basic imaging should be performed and appropriate imaging performed.

Pitfall

Alcohol intoxication is an independent risk factor for a positive CT result following minor head injury. 18 The more intoxicated the patient is the higher the likelihood of injury.19 Always consider occult head injury in patients presenting with confusion and agitation labelled as AWS.

Management 1- symptom triggered scoring systems

NICE recommends using a symptoms triggered treatment regime for management of AWS10 in the acute setting. These use scoring systems which assess the severity of the patients symptoms and guide dosage/frequency of pharmacological therapy. In the UK benzodiazepines, particularly diazepam, are the mainstay of treatment of AWS. These exert there effect by potentiating the activity of GABA which aims to restore balance between GABA/NDMA.9

Management 20 CIWA-Ar and GMAWS

Examples of symptom triggered scoring systems are the CIWA-Ar:

And the Glasgow Modified Alcohol Withdrawal Scale (GMAWS)17:

Essentially the more severe the symptoms the larger the dose of benzodiazepines and the more frequently the patient should be reassessed. Typical doses would be 10-20mg of Diazepam (or 1-2mg of Lorazepam) with repeat scoring in 1-2 hours.

Management 3 – Pharmacological therapy

NICE does not offer specific guidelines on special groups however the GMAWS protocol suggests10:

- Using lorazepam in patients with alcoholic liver disease (ALD) due to its shorter half life and potential reduced risk of oversedation

- Reduced benzodiazepine doses in patients with co-morbidities (COPD, reduced GCS, CVD, pneumonia, age >70, head injury and pregnancy). Reduce the dose by 50%.

- In patients unable to tolerate oral intake use an IV benzodiazepine at 50% of the oral dose (delivered by experienced staff and with appropriate monitoring for IV sedation)

Pitfall

There are significant differences between time half life and doses of different benzodiazepines. Generally speaking diazepam and chlordiazepoxide are thought of as long acting and lorazepam short acting.

Equivalent Doses: Diazepam 10mg= Lorazepam 1mg= Chlordiazepoxide 25mg17

Management 2 CIWA-Ar and GMAWS

A small subset of patients AWS will go on to develop severe AWS/DT. The rate of this is poorly defined in the literature with the incidence stated in the literature ranging from 8-33%.20,21 These patients can be violent and difficult to manage. NICE and the GMAWS protocol both recommend using parenteral benzodiazepines followed by parenteral haloperidol as a second line treatment.10,17 This treatment should only be delivered by clinicians experienced in IV sedation. These patients are at high risk of over sedation and complications and will likely require close observation and one to one nursing care.

Other treatments for benzodiazepine refractory AWS have been described in the literature such as phenobarbitoal,22,23 dexometamadine24,25 and ketamine26 however none of these are currently in widespread use in the UK.

A small subset of patients will require mechanical ventilation and IV propofol infusions due to the severity of their symptoms.27

Other complications of alcohol use disorder

Wernicke- Korsakoffs syndrome

Werncike- Korsakoffs syndrome is a neurological complication of chronic alcohol misuse caused by nutritional thiamine deficiency. Wernickes presents with confusion, ataxia, nystagmus and ophthalmoplegia. If untreated this can progress to Korsakoffs which is characterised by cerebellar ataxia, peripheral neuropathy and memory loss.7 Patients with Korsakoffs are classically described as exhibiting confabulation where they fabricate stories to fill in the gaps in their memory.

NICE recommend that patients who attend with malnourishment or decompensated liver disease and who have presented either to the emergency department or with an acute illness should be offered parenteral thiamine replacement.10

Refeeding syndrome

Patients who drink heavily are at risk of refeeding syndrome. Poor nutritional intake leads to changes in energy metabolism with the body sacrificing muscle stores of glycogen to maintain glucose levels. This causes depletion of potassium, magnesium and phosphate. When the patient is fed again (such as occurs on admission to hospital) these adaptations are rapidly reversed primarily by an increase in insulin levels.

This causes a large shift of extracellular potassium, magnesium and phosphate into cells. This shift gives rise to the clinical condition known as refeeding characterised by28:

- arrhythmia

- acute heart failure

- neurological disturbance- seizure, paraesthesia, muscle weakness and confusion

- respiratory failure

- renal failure secondary to ATN

NICE recommends that all patients at risk of refeeding should have electrolyte levels (U+Es/bone profile/Mg) regularly checked and be referred for review by a dietician. Electrolyte abnormalities should be corrected promptly.29

Hepatic Encephalopathy

Hepatic encephalopathy can occur in both chronic and acute liver failure. It is caused by the inability of the damaged liver to clear digested proteins (particularly ammonia) which are absorbed by the gut.

Increased serum ammonia causes direct inhibitory effects on neurones via its action on GABA and also causes brain oedema. This causes a syndrome of initial drowsiness with associated flapping tremor progressing to altered consciousness and then coma. Patients with severe encephalopathy can develop focal neurology such as pupillary signs and extensor posturing.

Diagnosis Is based on the clinical picture, imaging (CT/MRI can reveal evidence of brain oedema) and EEG. Serum ammonia can be measured but is not diagnostic alone for HE.

First line treatment is lactulose for HE secondary to both acute and chronic liver disease. In patients with chronic liver disease and recurrent HE the antibiotic rifaxamin can be added. Both of these work to alter the gut microbiome to reduce the amount of ammonia producing bacteria present. Underlying precipitants such as GI bleed and infection should be identified and corrected.30

- World Health Organization. Final report on implementation of the European Action Plan to Reduce the Harmful Use of Alcohol 20122020. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2020

- Hoskins R, Benger J. What is the burden of alcohol-related injuries in an inner city emergency department? Emerg Med J. 2013 Mar;30(3):e21.

- Public Health Scotland. Alcohol-related hospital statistics: Scotland financial year 2022/23. Edinburgh: Public Health Scotland; 2024 Mar 19.

- Foy A, Kay J, Taylor A. The course of alcohol withdrawal in a general hospital. QJM: An International Journal of Medicine, 1997, 90, pp. 253-261.

- Benzer DG. Quantification of the alcohol withdrawal syndrome in 487 alcoholic patients. J Subst Abuse Treat. 1990;7(2):117-23.

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th Edition. 2013.

- World Health Organization. Clinical descriptions and diagnostic requirements for ICD-11 mental, behavioural and neurodevelopmental disorders (CDDR). Geneva: WHO; 2024 Mar 8.

- Glass IB. Alcoholic hallucinosis: a psychiatric enigma1. The development of an idea. Br J Addict. 1989 Jan;84(1):29-41.

- Jesse S, Brthen G, Ferrara M, et al. Alcohol withdrawal syndrome: mechanisms, manifestations, and management. Acta Neurol Scand. 2017 Jan;135(1):4-16.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Alcohol-use disorders: diagnosis, assessment and management of harmful drinking (high-risk drinking) and alcohol dependence. NICE [CG115] 23 February 2011. Updated: 21 October 2014.

- Royal College of Emergency Medicine. Alcohol: A toolkit for Improving Care. 2015

- Maldonado JR, Sher Y, Das S, et al. Prospective Validation Study of the Prediction of Alcohol Withdrawal Severity Scale (PAWSS) in Medically Ill Inpatients: A New Scale for the Prediction of Complicated Alcohol Withdrawal Syndrome. Alcohol Alcohol. 2015 Sep;50(5):509-18.

- Wetterling T, Weber B, Depfenhart M, Schneider B, Junghanns K. Development of a rating scale to predict the severity of alcohol withdrawal syndrome. Alcohol Alcohol. 2006 Nov-Dec;41(6):611-5.

- Reoux JP, Malte CA, Kivlahan DR, Saxon AJ. The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) predicts alcohol withdrawal symptoms during inpatient detoxification. J Addict Dis. 2002;21(4):81-91.

- Dolman JM, Hawkes ND. Combining the audit questionnaire and biochemical markers to assess alcohol use and risk of alcohol withdrawal in medical inpatients. Alcohol Alcohol. 2005 Nov-Dec;40(6):515-9.

- Pecoraro A, Ewen E, et al. Using the AUDIT-PC to predict alcohol withdrawal in hospitalized patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2014 Jan;29(1):34-40.

- NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde. Management of alcohol withdrawal syndrome. Glasgow: GGC Medicines Handbook

- Haydel MJ, Preston CA, et al. Indications for computed tomography in patients with minor head injury. N Engl J Med. 2000 Jul 13;343(2):100-5.

- Johnston JJE, McGovern SJ. Alcohol related falls: an interesting pattern of injuries. Emergency Medicine Journal 2004;21:185-188.

- Lee JH, Jang MK, Lee JY, et al. Clinical predictors for delirium tremens in alcohol dependence. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005 Dec;20(12):1833-7.

- Wetterling T, Kanitz RD, Veltrup C, Driessen M. Clinical predictors of alcohol withdrawal delirium. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1994 Oct;18(5):1100-2.

- Rosenson J, Clements C, Simon B, et al. Phenobarbital for acute alcohol withdrawal: a prospective randomized double-blind placebo-controlled study. J Emerg Med. 2013 Mar;44(3):592-598.e2.

- Hjerm I, Anderson JE, Fink-Jensen A, Allerup P, Ulrichsen J. Phenobarbital versus diazepam for delirium tremensa retrospective study. Dan Med Bull. 2010 Aug;57(8):A4169.

- Crispo AL, Daley MJ, Pepin JL, Harford PH, Brown CV. Comparison of clinical outcomes in nonintubated patients with severe alcohol withdrawal syndrome treated with continuous-infusion sedatives: dexmedetomidine versus benzodiazepines. Pharmacotherapy. 2014 Sep;34(9):910-7.

- Frazee EN, Personett HA, et al. Influence of dexmedetomidine therapy on the management of severe alcohol withdrawal syndrome in critically ill patients. J Crit Care. 2014 Apr;29(2):298-302.

- Wong A, Benedict NJ, Armahizer MJ, Kane-Gill SL. Evaluation of adjunctive ketamine to benzodiazepines for management of alcohol withdrawal syndrome. Ann Pharmacother. 2015 Jan;49(1):14-9.

- Sohraby R et al. Use of propofol-containing versus benzodiazepine regimens for alcohol withdrawal requiring mechanical ventilation. Ann Pharmacother. 2014;48:456-461.

- Khan, L. Ahmed, J. Macfie, J. Refeeding syndrome: a literature review. 2010, Gastroenterology Research and Practice. 2011, pp 1-6

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Nutrition support for adults: oral nutrition support, enteral tube feeding and parenteral nutrition. Clinical guideline [CG32]. London: NICE; 2006 Feb 22. updated 2017 Aug 4.

- Wijdicks EF. Hepatic Encephalopathy. N Engl J Med. 2016 Oct 27;375(17):1660-1670.