Authors: Dean A Kerslake / Editor: Clifford J Mann / Reviewer: Mohamed Elwakil, Emma Everitt, Dean A Kerslake / Code: A3 / Published: 26/02/2021 / Reviewed: 05/08/2024

Prerequisites:

Before commencing this session you should have an understanding of the normal physiology of the liver.

Context

Acute liver failure is a rare presentation to emergency departments (EDs) in the UK, leading to around 400 admissions per year.

Paracetamol overdose accounts for approximately 60% of cases in the UK, whereas viral hepatitis is the most common cause worldwide. [1, 2]

Mortality is exceptionally high and ranges from 60-90%. Hyper acute presentation confers better prognosis with medical management whilst subacute cases have higher mortality without lover transplant.

Learning bite

Paracetamol is the commonest cause of acute liver failure in the Western world.

What is Acute Liver Failure?

The most widely accepted definition of acute liver failure is:

Evidence of coagulation abnormality (usually an international normalized ratio (INR) greater than or equal to 1.5) with any degree of mental alteration (encephalopathy) in a patient without pre-existing cirrhosis and with an illness of less than or equal to 26 weeks duration. Hyperacute liver failure has an onset of 7 days, acute liver failure 8-28 days and subacute 4-26 weeks. [1,2]

Acute on chronic liver disease is decompensation of liver function in a patient with chronic liver disease often precipitated by an event such as infection or gastrointestinal (GI) bleed.

Learning bite

It is important to differentiate acute liver failure from decompensation of chronic liver disease as prognosis and treatment differs.

Basic Science and Pathophysiology Causes and Manifestations

Acute liver failure is an inflammatory process causing massive hepatocellular necrosis.

Whilst the numerous causes of acute liver failure are heterogenous, the clinical presentation and general management is the same.

Causes:

Manifestations of Liver Dysfunction

| Normal function | Pathophysiological manifestations |

| Carbohydrate metabolism | Hypoglycaemia |

| Protein metabolism | Hyperammonemia and toxins causing encephalopathy |

| Bile secretion | Hyperbilirubinaemia causing jaundice |

| Drug detoxification | Drug toxicity |

| Synthesis and secretion of plasma proteins | Clotting factor deficiency causing coagulopathy Hypoalbuminaemia |

| Clearance of gut bacteria from portal system | Systemic infections resulting in sepsis |

| Sodium and water balance | Disruption leads to altered perception of volume status by kidneys and subsequent renal failure |

History

Often there is very little history available, however it should focus mainly on:

- risk factors for viral hepatitis such as IV drug use, recent tattoos, travel and sexual histories

- family history of Wilsons or haemochromatosis

- Exposure to viruses, drugs or toxins but can often be non specific with symptoms of anorexia or vomiting

- Recent GI upset can point to mushroom poisoning

- Recent shock/arrest can point towards acute ischaemic injury

- Breast cancer, melanoma, lymphoma and small cell cancers can give rise to malignant infiltration

- Active malignancy can also be responsible for Budd Chiari syndrome

- Patients with severe encephalopathy, the history may be limited or unavailable

Examination

You should examine for encephalopathy and jaundice. Right upper quadrant pain may be present. Signs of chronic liver disease would suggest either acute on chronic liver failure or decompensated liver disease.

Signs of chronic liver disease include:

- Clubbing

- Leukonychia

- Palmar erythema

- Asterixis

- Spider naevi

- Scratch marks

- Loss of secondary sexual characteristics

- Hepato/splenomeglay

- Ascites

- Oedema

- Kayser-Fleisher rings (Wilson disease),

- Features of preeclampsia (HELLP syndrome)

Fig 1 Someone with jaundice, a sign of chronic liver disease (Reproduced with permission from CDC/Dr. Thomas F. Sellers/Emory University)

Risk Stratification

High mortality exists amongst all patients.

Although current scoring systems do not accurately predict the outcome or need for transplantation, there are some factors associated with a poorer outcome. For example, in some patient groups less than 25% survive without transplant, compared to more than 50% in other others [1].

Factors Associated with a poor outcome:

Aetiology |

|

| Admission COMA | Grade III or IV |

INR |

> 6.5 |

Prediction of the need for transplant in paracetamol as aetiology:

| Admission COMA | Grade III or IV |

| pH | < 7.3 following fluid resuscitation |

| INR | > 6.5 |

| Creatinine | > 300 |

The Kings College Criteria (shown above for paracetamol) have also been used as tool to predict need for transplant [1,2,3].

It must be recognised that whilst it has good specificity, it has relatively poor sensitivity and clinical judgement must prevail.

Learning Bite

Certain aetiologies, COMA and significantly deranged prothombin times put patients into a group more likely to require transplantation.

In the ED remember the three Rs:

- Recognise

- Resuscitate

- Refer

1. Recognise

Prompt recognition is essential. Look out for:

- Unexplained acidosis

- Confusion

- Shock

- Hypoglycaemia

- Coagulopathy

- Deranged LFTs

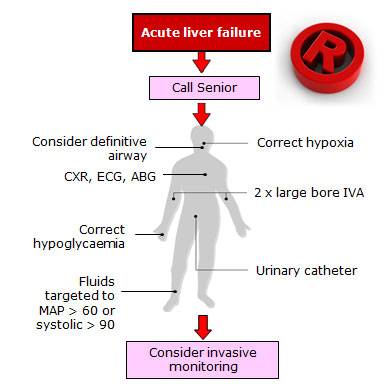

2. Resuscitate

- Consider Intubation if unable to protect or maintain airway or poor oxygenation or ventilation

- Give oxygen to correct hypoxia

- Give fluids for hypotension with evidence of poor end organ perfusion

- Maintain normogylcaemia

Adjuncts

- Urinary catheter

- ABG

- CXR

Other investigations and monitoring as required.

3. Refer

Involve

- Regional transplant teams

- Gastroenterology teams

- Intensive care teams

Critical Care Management Overview

The aetiology should be sought and treated in all cases.

Treatment is mainly supportive and consists of end organ support until a transplant becomes available or liver function improves.

Learning Bite

Critical care management in a specialist tertiary referral unit is recommended for most patients with acute liver failure.

Four Grades of Encephalopathy

| Grade I | Changes in behaviour with minimal change in level of consciousness |

| Grade II | Gross disorientation, drowsiness, possibly asterixis, inappropriate behaviour |

|

|

Grade III |

Marked confusion, incoherent speech, sleeping most of the time but rousable to vocal stimuli |

Grade IV |

Comatose, unresponsive to pain, decorticate or decerebrate posturing |

|

|

Management of other complications of acute liver failure

The following checks and treatment should be carried out:

Sepsis

Regular surveillance and culturing for occult or frank sepsis.

Prophylactic antibiotics and antifungals do not improve outcome but may occasionally be considered.

In the highest risk for cerebral edema, the prophylactic induction of hypernatremia with hypertonic saline to a sodium level of 145-155 mEq/L is recommended

Coagulopathy

| Most centres routinely give vitamin K but give | |

| FFP only if | active bleeding and INR >1.5 or INR >7 |

| Platelets if | <10, 000 or <50 000 and needing invasive procedure or bleeding |

This is used as a marker of liver function therefore should not be routinely corrected [1].

GI Bleeding

Give prophylactic H2 blockers to all ventilated patients as evidence shows they reduce the incidence of GI bleeds [1].

Learning Bite

Critical care management in a specialist tertiary referral unit is recommended for most patients with acute liver failure.

Haemodynamic Support

Maintain adequate intravascular volume.

Use CVVH for acute renal failure.

Systemic Vasopressors may be required to keep MAP >60-65.

Learning Bite

Critical care management in a specialist tertiary referral unit is recommended for most patients with acute liver failure.

Metabolic Concerns

Commence early nutritional support (preferably enteral otherwise parenteral).

Correct levels for:

- Glucose

- Magnesium

- Phosphate

- Potassium

Learning Bite

Critical care management in a specialist tertiary referral unit is recommended for most patients with acute liver failure.

Transplant

List patient early if poor prognostic factors or predicted clinical course.

Learning Bite

Critical care management in a specialist tertiary referral unit is recommended for most patients with acute liver failure.

Aetiology Speciifc Management

Aetiology specific management for the various causes of ALF is shown below:

Aetiology |

Treatment |

Further Action |

| Paracetamol poisoning | Activate charcoal within 1 hour N-acetylcysteine even if >48 hours or if paracetamol poisoning cannot be excluded. (has been shown to decrease mortality even in established hepatotoxicity) |

|

| Mushroom poisoning | Penicillin G and silymarin.Consider administration of N-acetylcysteine | List for transplant |

| Drug reactions | Discontinue any possible offending drugs | |

| Viral Hepatitis | Acyclovir if HSV/VZV suspected | |

| Wilsons disease | List for transplant | |

| Autoimmune Hepatitis | Corticosteroids | List for transplant |

| HELLP | Delivery of unborn child | |

| Acute Ischaemic injury | Cardiovascular support | |

| Budd Chiari Syndrome | List for transplant if malignancy excluded | |

| Malignant Infiltration | N/A | |

| Indeterminate | N/A |

There are however some hidden hazards that should be avoided:

- Failing to differentiate between acute liver failure and decompensated chronic liver failure

- Failing to appreciate the severity and likely clinical deterioration of patients with acute liver failure

- Missing the subtle signs of grade I encephalopathy

- Failing to alert the transplant and ICU teams early

- Failing to maintain a high index of suspicion for paracetamol poisoning in all acute liver failure patients

- Consideration to administration of N-acetylcysteine to all patients in whom paracetamol poisoning cannot be confidently ruled out

Key Learning Points

- Paracetamol toxicity is the commonest cause of acute liver failure in the developed world

- Evidence of chronic liver disease suggests acute on chronic liver failure rather than acute liver failure and this has prognostic implications

- History should focus mainly on exposure to viruses, drugs or toxins

- Aetiology, grade III or IV encephalopathy or an INR >6.5 put patients into a higher risk group (grade III recommendation)

- The Kings college criteria can be used to predict the need for transplant and has good specificity but poor sensitivity but clinical judgement must still prevail (grade III recommendation)

- All patients should get a full blood count, urea and electrolytes, glucose, liver function tests, INR, Group & Save and arterial blood gases and consideration of a CT Head if encephalopathy is present

- Further tests may include paracetamol assay, virus serology, autoimmune tests, ceruloplasmin, CT, flow imaging or biopsy

- Early recognition, resuscitation and referral to intensive care are essential components of emergency department treatment

- Give N-acetylcysteine to all patients if paracetamol poisoning cannot be excluded (grade II recommendation)

- Look for signs of raised intracranial pressure, sepsis, coagulopathy, gastrointestinal bleeding, renal failure and metabolic abnormalities and treat appropriately (grade III recommendation)

- Lee WM, et al. AASLD position paper: The management of Acute Liver Failure: Update 2011. Journal of Hepatology. Sept 2011: 1-22.

- Stravitz RT, Kramer AH, Davern T. Intensive care of patients with acute liver failure:

recommendations of the U.S. Acute Liver Failure Study Group. Crit Care Med 2007;35:2498-2508 - Aziz R, Price J, Agarwal B. Management of acute liver failure in intensive care. BJA Educ. 2021 Mar;21(3):110-116.