Author: Adrian Robert Marsh / Editor: Nicola McDonald / Reviewer: Peter Kilgour, Adrian Robert Marsh / Codes: A2 / Published: 17/05/2021 / Reviewed: 05/09/2024

Definition

The word stridor is derived from the Latin stridulus, which means creaking, whistling or grating. It is a sign of airway obstruction.[1,2]

Croup is a syndrome consisting of cough, stridor, hoarseness and varying degrees of difficulty breathing.

Basic science and pathophysiology of stridor

The Mechanics of Breathing

The mechanics of breathing in a child are influenced by their anatomy. The chest wall is compliant as the ribs are cartilaginous in nature and lie more horizontally than in an adult. In addition, the accessory muscles are immature and the diaphragm can become easily fatigued. An increase in inspiratory effort causes tracheal tug, intercostal muscle in-drawing and sternal recession, all of which reduce mechanical efficiency.

Children have a small functional residual lung capacity with little respiratory reserve. In times of increased oxygen demand and an increased metabolic demand, children can decompensate quickly.

Presentation of Acute Stridor

Stridor is a harsh, vibratory sound produced from turbulent airflow through the respiratory passages. It is normally heard on inspiration but can be heard on expiration and sometimes can be biphasic. Click here to listen to an example of a child with croup.

Stridor is a symptom, not a diagnosis, and the underlying cause must be determined. It may be inspiratory (most common), expiratory, or biphasic, depending on its timing in the respiratory cycle, and the three forms each suggest different causes, as follows:

- Inspiratory stridor suggests a laryngeal obstruction

- Expiratory stridor implies tracheobronchial obstruction

- Biphasic stridor suggests a subglottic or glottic anomaly

Causes of acute onset of stridor. Please add the following to the start of this section.

The acute causes of new on set stridor include

- Infections such as croup, epiglottitis, peritonsillar abscesses, and retropharyngeal abscesses

- Ingestion of foreign objects or food

- Ingestion of toxic chemicals

- Airway burns

- Injuries to the jaw or neck

The volume of stridor does not correlate with the degree of obstruction.

Poiseuilles Law

The underlying pathology is inflammation of the pharanx, larynx, trachea or bronchi. Poiseuilles Law states that if the radius of the airway is halved then the resistance in the airflow increases by 16-fold. [3] It is the subglottic inflammation and swelling that compromises the airway in croup.

Learning bite

A small reduction in the diameter of the airway dramatically reduces the airflow and the child can rapidly deteriorate.

Epidemiology of croup

Approximately 80% of children presenting with an acute onset of stridor and a cough have croup. [4]

Croup is a clinical syndrome of a hoarse voice, harsh barking cough (often described as seal-like) and acute inspiratory stridor.

Croup occurs in 2% of children aged between 6 and 36 months, with a peak incidence at 12 to 24 months. There is a male to female ratio of 3:2. It is more common in the spring and autumn months but can occur at any time of year.

Typically, there is a preceding coryzal illness with croup developing over several days. The symptoms are classically worse at night and typically last between 3 and 5 days but can last up to a week. [5]

Learning Bite

Croup is the most common cause of acute stridor.

In 80% of cases the cause of croup is viral and the majority are parainfluenza viruses. Other viruses that cause croup are adenovirus, respiratory syncytial virus, measles, coxsackie, rhinovirus, echovirus, reovirus and influenza A and B [5].

Westley Croup Score

The Westley croup score is validated and commonly used in clinical practice (Table 1). Children with croup can be divided into four levels of severity [7,8]:

- Mild (croup score 0-2)

- Moderate (croup score 3-5)

- Severe (croup score 6-11)

- Impending respiratory failure (croup score 12-17)

85% of children have mild croup. Around 5% of children with croups require admission to hospital and of these 1-3% require intubation. In a 10-year study of those intubated there was 0.5% mortality rate. Uncommon complications include pneumonia and bacterial tracheitis. [9]

| Score | Stridor | Retractions | Air Entry | SaO2 <92% | Level of consciousness |

| 0 | None | None | Normal | None | Normal |

| 1 | Upon agitation | Mild | Mild decrease | ||

| 2 | At rest | Moderate | Marked decrease | ||

| 3 | Severe | ||||

| 4 | Upon agitation | ||||

| 5 | At rest | Decreased |

Assessment of a Child Presenting With Croup

If possible, allow the child to sit on carers lap and do not examine the throat.

The history is of key importance and in croup the following is the typical presentation[10]:

- One to two days of an upper respiratory tract infection followed by a barking cough and stridor.

- Low grade fever

- No drooling

The following clinical signs are often present[10]:

- Stridor

- Barking cough

- Hoarseness

- Respiratory distress +/- fever +/- coryzal symptoms

Assessment of severity is based on assessment of the following parameters[10]:

- Respiratory Rate

- Heart Rate

- Oxygen Saturations

- Respiratory Distress

- Exhaustion

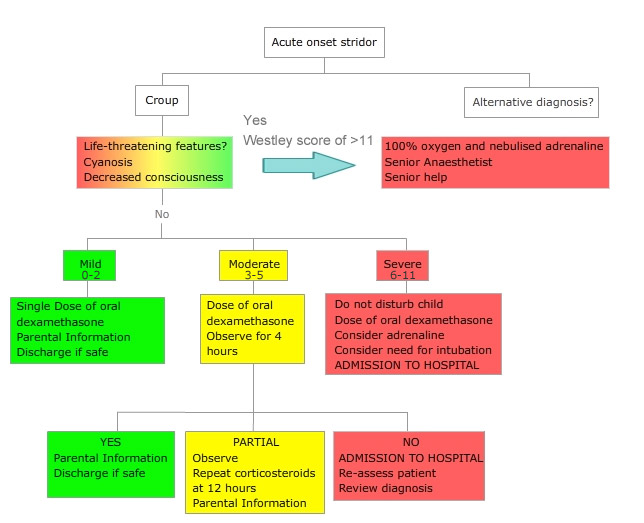

Algorithm for assessing and managing a child presenting with croup:

Treatment

Children with croup should be made comfortable and care should be taken to avoid agitating the child, such as using a non-contact form of oxygen delivery e.g. allowing the childs care-giver to deliver oxygen using a wafting technique. Oxygen should be administered to any child with oxygen saturation <92% on air.

In the 19th century steam and mist therapy were used. There is no published evidence to support its use and small trials failed to show an improvement in oxygen saturations, respiratory rate, heart rate or croup score. In addition, there have been cases reported of scald injuries in children treated with hot humidified air. [11-13]

The aetiology of croup is viral and therefore antibiotics are not indicated. Bacterial tracheitis and pneumonia following croup are rare; occurring in less than one in a thousand cases.

Nebulised adrenaline

Nebulised adrenaline is only used in children with severe and life-threatening croup.

Treatment is with 0.5 mL/kg of 1:1,000 concentration to a maximum dose of 5 mL.

Double blind randomised control trials of this treatment demonstrate an improvement within 30 minutes and last up to 2 hours. As the effect wears off, the childs symptoms return to base line level, however, a proportion of children deteriorate even further. [7,14,15]

However, Adrenaline does allow time for an experienced team including a senior anaesthetist to be gathered as well as rapidly improving the patients distress.

The benefit of using corticosteroids

There are numerous well-designed trials and reviews that clearly demonstrate clinical benefit of corticosteroids irrespective of severity. In children with severe or impending respiratory failure, there is an absolute risk reduction of 1.1% in the rate of intubation. [16]

Oral dexamethasone

Oral dexamethasone 0.15 mg/kg has been shown to be superior to prednisolone at a dose of 1 mg/kg. An equivalence trial demonstrated a re-presentation rate of 29% in the prednisolone group compared to 7% in the dexamethasone group. [17]

There is no difference in efficacy between oral and intramuscular dexamethasone.

If the child is vomiting, 2 mg of nebulised budesonide can be used. However, nebulised budesonide can agitate the child whilst being delivered and taking into account the cost of equipment required as well as budesonide being more expensive, dexamethasone is the preferred treatment. [17-20]

Trial data

A meta-analysis of trials demonstrated a reduction in the croup score of three points by six hours in those treated with dexamethasone and by one point in those treated with budesonide.

There was also a reduction in the number of children requiring rescue treatment with nebulised adrenaline of 9% and 12% in those treated with budesonide and dexamethasone respectively.

In addition, the length of time spent in the emergency department (ED) was reduced as was the admission rate in those treated with dexamethasone or budesonide. [21]

Oral dexamethasone dose

The Cochrane review [22] concluded that a dose of dexamethasone of 0.15 mg/kg compared to 0.6 mg/kg did not find any important difference between croup scores at 2, 6 or 12 hours, return visits or (re)admission of children, length of stay in the hospital.

Local protocols should be followed for dosing.

Learning bite

- The mainstay of treatment for croup is corticosteroids, which take between 2 and 4 hours to have a clinical effect.

Monitoring

The respiratory rate, work of breathing, oxygen saturation and pulse rate should be carefully monitored. The work of breathing, respiratory rate, volume of stridor and pulse rate should decrease if the treatment is working.

How can work of breathing be assessed and quantified?

Measuring the work of breathing requires complex instrumentation, measuring it in patients with acute serious illness is difficult and risky. Instead, physicians determine if the work of breathing is increased by examining the patient looking for signs of increased breathing effort. These signs include nasal flaring, the contraction of sternomastoid, and thoraco-abdominal paradox (see-saw breathing).

Children with mild croup should be observed for a minimum of 2 hours and those with moderate croup should be observed for a minimum of 4 hours following administration of Dexamethasone.

Complications

Despite early treatment of croup with steroids, some children do not respond and can deteriorate. Nebulised adrenaline causes a dramatic short term improvement in symptoms but in some patients there is a rebound effect with rapid deterioration.

Referral to a senior paediatric trained doctor and early consideration of PICU involvement is essential.

Eighty five percent of children have mild croup. Five percent of children are admitted into hospital and of these 1-3% require intubation. In a 10 year study of those intubated there was 0.5% mortality rate. Uncommon complications include pneumonia and bacterial tracheitis [9].

Discharge

Those with moderate croup need to be observed for a minimum of four hours following a dose of dexamethasone and then re-assessed.

Those with severe croup must be admitted. In children discharged home, advice must be given to a parent and documented in the notes:

Discharge advice to parents and carers

Croup is a viral illness that is characterised by a barking cough and noisy breathing. Croup can re-occur. This illness typically lasts 3-4 days.

Your child has been given a dose of steroids. In mild cases one dose is normally enough. In moderate cases a second dose may be given 12 hours after the first dose.

In mild croup, your child has a barking cough but does not usually have noisy breathing at rest or is not having problems breathing. Mild croup can usually be managed at home with the following:

- Try and calm your child, as breathing is more difficult when your child is upset

- If your child has a fever and is miserable give paracetamol (Calpol)

- Croup can be worse at night; your child may be more settled if someone stays with them

You should return to the Emergency Department immediately if:

- Your childs breastbone sucks in when breathing in

- If your child is struggling to breath

- If you child has noisy breathing

- If your child is drinking less than 50% of normal or is having dry nappies

- You are worried for any reason

Further information: Croup Healthier Together

Differential Diagnosis

Stridor in a child can be acute or chronic. Table 2 shows the common causes of acute and chronic stridor. The diagnosis and treatment of the causes of chronic stridor are outside the scope of this module.

| Acute Stridor | Chronic Stridor | |||

Excluding croup, the most likely causes of acute stridor are:

|

|

|||

Foreign Body

Food is the most common foreign body aspirated and has a peak incidence at age 1-2 years.

The usual history obtained is of sudden onset coughing, retching and choking. Initial treatment of a choking child is as per APLS protocols.

Partial obstruction above or at the vocal cords causes inspiratory stridor, a change in voice, cough and dyspnoea.

Partial obstruction of the lower airway in addition to cough and dyspnoea may cause a pneumothorax, pneumomediastinum or surgical emphysema.

Findings on examination will depend on the site of the obstruction. Findings include cough, wheeze, stridor and pneumonia but there may be a normal examination. An inspiratory chest x-ray may be normal, whilst an expiratory film may demonstrate air trapping. [23, 24]

Treatment is by removal of the foreign body under general anaesthetic with a rigid bronchoscope.

Click the thumbnail to see an algorithm for treating a choking child.

Angioedema

Angioedema, with or without urticaria, is classified as allergic, hereditary, or idiopathic.

Allergic and idiopathic angioedema

Allergic angioedema (IgE mediated) and idiopathic, is caused by mast cell degranulation causing release of histamine, prostaglandins, leukotrienes and thromboxanes.

There may not be a preceding history of allergy or the patient may not be able to recall the exposure to the allergen.

More than 90% of patients have some combination of urticaria, erythema, pruritus, or angioedema. Airway compromise is caused by the resultant vasodilatation and associated oedema.

Immediate treatment is with an age-based dose of intramuscular adrenaline as per the algorithm below. Other beneficial treatments include oxygen, steroids, H1 and H2 blockers, IV fluids and consideration of intubation.

If adrenaline is required, the child must be admitted for observation due to the risk of re-occurrence after six hours. This is 6 hours after the symptoms have resolved and that this is due to the risks of biphasic anaphylaxis that occurs in up to 4.5% [26] of allergic reaction with and average time between reactions of 6-10 hours (Mean 8.13. [27]

On discharge, children should be referred to an allergy specialist; receive training on the use of an adrenaline auto-injector e.g. Epipen or Anapen and be discharged with two adrenaline auto-injectors, one of which should be kept at school.

Click the thumbnail to see the algorithm on anaphylaxis.

Learning bite

Adrenaline is the first pharmacological intervention with a child with anaphylaxis.

Heredetary angioedema

Hereditary angioedema (HAE) is an autosomal dominant disorder of C1 inhibitor. Oedema formation is related to the reduction or dysfunction of C1 inhibitor which results in the release of bradykinin and C2-kinin mediators. This enhances vascular permeability and leads to extra-vascular fluid shifts. [29]

Approximately 40% of people with HAE present with the first episode before the age of 5 years and 75% present before age 15 years. Attacks normally occur at a single site. The life time risk of laryngeal involvement during an attack is about 70%, although uncommon in children. [30] Other presentations are subcutaneous angioedema and abdominal attacks.

Subcutaneous angioedema is circumscribed, non-puritic and non-erythematous swelling of the skin. Almost 100% of patients with HAE will experience this in their lifetime. 45% of attacks involve the limbs but can also develop on the face, neck, genitals and trunk. Skin oedema occurs in 50% of all attacks. Abdominal attacks mimic an acute abdomen with abdominal pain, vomiting, diarrhoea and even ileus. [31]

For severe HAE attacks i.e. facial, tongue, oropharyngeal swelling, dysphagia, voice alteration, or severe abdominal pains; administration of C1 inhibitor concentrate is the treatment of choice (table 3). Clinical improvement is seen within 15 to 60 minutes. A repeat dose may be required if symptoms are not relieved within an hour. [32] If C1 inhibitor concentrate is not available then fresh frozen plasma (10 ml/kg) or solvent detergent treated plasma (Octaplas) can be used. [33]

Table 3: Dose of C1 inhibitor concentrate

Learning Bite

HAE does not respond to adrenaline.

Abscess

A retropharyngeal abscess forms in the potential space between the prevertebral fascia posteriorly, the posterior pharyngeal wall anteriorly, the carotid sheaths anteriorly, the base of the skull superiorly and the mediastinum inferiorly.

The origin is spread of infection from the teeth, middle ear or the sinuses. Peritonsillar abscess forms in the potential space between the palatine tonsil and the capsule. It can spread to include the masseter muscles and the pterygoid muscle.

The bacteria most commonly identified are streptococcus pyogenes, staphylococcus aureus, haemophilus influenzae and neisseria species and anaerobes. [34,35]

Both present similarly with fever, sore throat and poor oral intake. Examination may reveal a neck mass, fever, cervical adenopathy, neck stiffness or torticollis, agitation, lethargy, drooling, trismus and stridor. In stable patients lateral soft tissue x-rays can show an enlarged prevertebral soft tissue shadowing.

Children with airway compromise must be admitted for close monitoring with urgent incision and drainage of the abscess.

Epiglottitis

Following the introduction of the Haemophilus influenza type b (Hib) vaccination in 1992, childhood epiglottitis has become rare. It can also be caused by the same aerobes that cause peri-tonsillar abscesses. However, children who are fully immunised can still get Hib culture positive epiglottitis.

Onset

There is a rapid onset of pyrexia, sore throat, muffled speech, drooling and stridor. The child usually looks unwell; sitting forwards, mouth open, drooling with tongue protruding. [36]

The child should reassured. Do not attempt any intervention that upsets the child nor should you undertake oropharyngeal inspection as this could precipitate complete airway obstruction.

Management

Management of this condition remains controversial. The cornerstone is not to distress the child as this can precipitate complete airway obstruction.

Oxygen should be administered if the child is hypoxic.

In the first instance, intravenous antibiotics should be administered, if intravenous access can be achieved without distress.

Treatment choice is by hospital guideline with a third-generation cephalosporin being a reasonable choice.

Children under 6 years of age require urgent intubation, ideally in theatre by an experienced anaesthetist with an ENT surgeon present. [37] If there is no time to transfer the child to theatre, then a difficult intubation trolley and cricothyroidotomy kit must be ready.

In those over the age of 6 years, observation may be an option following consultation with an ENT and PICU consultant. The average time for children to remain intubated is 48 to 96 hours. Extubation occurs when direct visualisation of the epiglottis confirms that the inflammation of the epiglottis and surrounding tissues has resolved. [38]

Tracheitis

In this condition, the larynx, trachea and bronchi can become obstructed with purulent debris. There is an adherent pseudomembrane that forms over the tracheal mucosa that can slough off causing an obstruction. There is normally a preceding upper respiratory tract infection for a couple of days, followed by a rapid deterioration with a pyrexia and respiratory distress. There is a cough producing copious secretions and retrosternal pain. There is no dysphagia or drooling – unlike epiglottitis.

Causative organisms

The most common causative organisms are:

- Staphylococcus aureus (41%)

- Haemophilus influenzae (18%)

- Streptococcus pneumoniae (15%)

- Moraxella catarrhalis (13%)

- Streptococcus pyogenes (9%).

Treatment

Treatment is with intravenous antibiotics.

Endotracheal intubation is often needed for airway control, management of respiratory failure and pulmonary toilet.

Young children can deteriorate quickly due to the smaller size of the airway. Full recovery with no long-term morbidity is expected in the vast majority of children.

Complications

The most frequent complication associated with the acute phase of illness is pneumonia.

- Less common complications include

- Acute respiratory distress syndrome

- Septic shock

- Pulmonary oedema

- Pneumothorax

- Cardiorespiratory arrest (rarely)

Long-term morbidity associated with bacterial tracheitis is minimal. As treatment in the acute phase of the illness frequently requires insertion of an endotracheal tube into an inflamed airway, the potential for the subsequent development of subglottic stenosis is well recognised. [39]

Comparison between Croup, Epiglottitis and Tracheitis

Table 4 presents a comparison between croup, epiglottitis and tracheitis.

| Croup | Epiglottitis | Tracheitis | |

| Incidence | Common | Rare | Rare |

| Age | 6 months 3 years | 27 years | 6 months- 14 years |

| Aetiology | Viral | Bacterial | Bacterial |

| Speed of onset | Slow | Very rapid | Rapid |

| Fever | Rarely >39 degrees | Normally >39 degrees | Normally >39 degrees |

| Cough | Barking | Suppressed | Present |

| Voice | Hoarse | Muffled | Hoarse |

| Position | Supine | Sitting forward, neck extended | Supine |

| Neck X-Ray AP | Steeple sign* | Normal | Steeple sign* |

| Neck X-Ray Lateral | Normal | Thumb print | Hazy |

| Response to adrenaline | Very good | No response | Partial or no response |

| *Steeple sign: On anteroposterior radiographs of the soft tissue of the neck the lateral convexities of the subglottic trachea are lost and narrowing of the subglottic lumen produces an inverted ‘V’ pattern, resembling a church steeple [45]. | |||

Fig.1 Steeple sign via epomedicine.com

- 20% of children presenting with acute stridor do not have croup. If an alternative diagnosis is not sought then serious differentials could be missed.

- In children who present with a sudden onset of stridor a foreign body should be considered.

- Children with epiglottitis should not have the oropharynx examined as this can cause total airway obstruction. Diagnosis is clinical and confirmed when the child is intubated.

- In a patient presenting with anaphylactic symptoms that do not respond to adrenaline hereditary angioedema should be considered. Hereditary angioedema does not respond to adrenaline and C1 inhibitor concentrate should be given. Fresh frozen plasma should be used taking care not to cause fluid overload and pulmonary oedema.

- Benson BE. Stridor. Medscape, Updated in 2024.

- Leung AK, Cho H. Diagnosis of stridor in children. Am Fam Physician. 1999 Nov 15;60(8):2289-96.

- West JB, Luks AM. Wests respiratory physiology: The essentials. 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2015.

- Maloney E, Meakin GH. Acute stridor in children. Continuing Education in Anaesthesia, Critical Care and Pain. 2007 Dec;7(6):183-186.

- Fitzgerald DA, Kilham HA. Croup: assessment and evidence-based management. Med J Aust. 2003 Oct 6;179(7):372-7.

- Rihkanen H, Rnkk E, Nieminen T, Komsi KL, et al. Respiratory viruses in laryngeal croup of young children. J Pediatr. 2008 May;152(5):661-5.

- Klassen TP, Rowe PC. The croup score as an evaluative instrument in clinical trial. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 1995; 149: 60-1.

- Westley CR, Cotton EK, Brooks JG. Nebulized racemic epinephrine by IPPB for the treatment of croup: a double-blind study. Am J Dis Child. 1978 May;132(5):484-7.

- McEniery J, Gillis J, Kilham H, Benjamin B. Review of intubation in severe laryngotracheobronchitis. Pediatrics 1991; 87: 847-53.

- Foster S. Croup. NHSGGC Paediatrics for Health Professionals, 2017.

- Neto GM, Kentab O, Klassen TP, Osmond MH. A randomized control trial of mist in the acute treatment of moderate croup. Acad Emerg Med 2002; 9(9): 873-79.

- Bouchier D, Dawson KP, Fergusson DM. Humidification in viral croup: a controlled trial. Aus Paed Jour 1984; 20(4): 289-91.

- Moore M, Little P. Humidified air inhalation for treating croup: a systemic review and meta-analysis. Family Practice 2007; 24: 295-301.

- Gardner HG, Powell KR, Roden VJ, Cherry JD. The evaluation of racemic epinephrine in the treatment of infectious croup. Pediatrics 1973; 52: 52-55.

- Aregbesola A, Tam CM, Kothari A, et al. Glucocorticoids for croup in children. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2023, Issue 1. Art. No.: CD001955.

- Kairys A, Marsh-Olmstead E, OConner G. Steroid treatment of laryngotracheitis: a meta-analysis of the evidence from randomised trials. Pediatrics 1989; 83: 983-93.

- Sparrow H, Geelhoead GC. Prednisolone versus dexamethasone in croup: a randomised equivalence trial. Arch Dis Child 2006; 91: 580-83.

- Klassen TP, Watters LK, et al. The efficacy of nebulized budesonide in dexamethasone-treated outpatients with croup. Pediatrics. 1996 Apr;97(4):463-6.

- Johnson DW, Jacobson S, Edney PC, Hadfield P, Mundy ME, Schuh S. A comparison of nebulized budesonide, intramuscular dexamethasone, and placebo for moderately severe croup. N Engl J Med 1998;339(8):498-503.

- Cetinkaya F, Tufekci BS, Kutluk G. A comparison of nebulized budesonide, and intramuscular, and oral dexamethasone for treatment of croup. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2004;68(4): 453-56.

- Ausejo M, Saenz A, Pham B, et al. The effectiveness of glucocorticoids in treating croup: meta-analysis. BMJ. 1999 Sep 4;319(7210):595-600.

- Aregbesola A, Tam CM, Kothari A, et al. Glucocorticoids for croup in children. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2023, Issue 1. Art. No.: CD001955.

- Tan HK, Brown K, McGill T, et al. Airway foreign bodies (FB): a 10-year review. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2000 Dec 1;56(2):91-9.

- Zerella JT, Dimler M, McGill LC, Pippus KJ. Foreign body aspiration in children: value of radiography and complications of bronchoscopy. J Pediatr Surg. 1998 Nov;33(11):1651-4.

- Paediatric Choking Algorithm 2021. Paediatric basic life support Guidelines, Resuscitation Council UK

- Rohacek M, Edenhofer H, Bircher A, Bingisser R. Biphasic anaphylactic reactions: occurrence and mortality. Allergy. 2014 Jun;69(6):791-7.

- Mack DP. Biphasic anaphylaxis: a systematic review of the literature. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol [Internet]. 2014;10(S1).

- Emergency treatment of anaphylaxis. Guidelines for healthcare providers. Working Group of Resuscitation Council UK, May 2021.

- Agostoni A, Aygren-Prsn E, Binkley KE, Blanch A, et al. Hereditary and acquired angioedema: problems and progress: proceedings of the third C1 esterase inhibitor deficiency workshop and beyond. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004 Sep;114(3 Suppl):S51-131.

- Zuraw BL. Clinical practice. Hereditary angioedema. N Eng J Med 2008; 359(10): 1027-36.

- Bork K, Staubach P, Eckardt AJ, Hardt J. Symptoms, course, and complications of abdominal attacks in hereditary angioedema due to C1 inhibitor deficiency. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006; 101: 619-27.

- Farka H, Varga L, Szeplaki G, Visy B, Harmat G, Bowen T. Management of Hereditary Angioedema in Pediatric Patients. Pediatrics 2007; 120: 713-22.

- Hill BJ, Thomas SH, McCabe C. Fresh frozen plasma for acute exacerbations of hereditary angioedema. Am J Emerg Med. 2004; 22: 633 .

- Jousimies-Somer H, Savolainen S, et al. Bacteriologic findings in peritonsillar abscesses in young adults. Clin Infect Dis. 1993 Jun;16 Suppl 4:S292-8.

- Prior A, Montgomery P, Mitchelmore I, Tabaqchali S. The microbiology and antibiotic treatment of peritonsillar abscesses. Clini Otolaryngol 1995; 20: 219-23.

- Depuydt S, Nauwynck M, Bourgeois M, Mulier JP. Acute epiglottitis in children: a review following an atypical case. Acta Anaesth Belg 2003; 54: 237-41.

- Stroud RH, Friedman NR. An update on inflammatory disorders of the pediatric airway. Epiglottis, croup and tracheitis. Am J Otolaryngol 2001; 22: 268-75.

- Crysdale WS, Sendi K. Evolution in the management of acute epiglottitis: a 10-year experience with 242 children. Int Anesthesiol Clin 1988; 26: 32-8.

- Al-Mutairi B, Kirk V. Bacterial tracheitis in children: Approach to diagnosis and treatment. Paediatr Child Health 2004; 9(1): 2530.

- Salour M. The steeple sign. Radiology. 2000 Aug;216(2):428-9.

- Paediatric advanced life support Guidelines. Resuscitation Council UK, 2021.

- Adult advanced life support Guidelines. Resuscitation Council UK, 2021.

- Stridor. Patient, Updated in 2020.