Author: Oliver Daly / Editor: Louisa Mitchell / Reviewer: Jennifer Lockwood, Mehdi Teeli, Jia Luen Goh / Codes: / Published: 18/10/2021 / Reviewed: 13/02/2025

This session will provide you with information on Pancreatitis, including the diagnosis, basic science, assessment and management.

Context

Pancreatitis is a common presentation to the emergency department (ED).

Across the whole of the UK the same appears to be true and incidence ranges from 150-420 cases per million population. [1-2]

Most patients will have a mild disease that resolves spontaneously, however, some can be significantly unwell requiring high dependency unit (HDU) or intensive care unit (ICU) level care for single or multiple organ failure.

Unfortunately it can be difficult to detect those patients at risk of complications early in their presentation and thus rapid assessment, severity prediction, early referral and effective initial management are vital.

Mortality rates

The overall mortality in acute pancreatitis is approximately 5%, and is:

- 3% in interstitial pancreatitis

- 17% in necrotising pancreatitis (30% in infected necrosis, 12% in sterile necrosis). [1]

The UK working group for pancreatitis has stated that mortality should be less than 10% for all cases of pancreatitis, with less than 30% for severe cases.

Gallstone pancreatitis is more common in white women >60 years of age, especially among patients with microlithiasis. Alcoholic pancreatitis is seen more frequently in men.

Learning Bite

Pancreatitis carries a significant mortality rate.

Definition

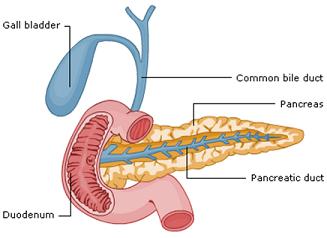

The pancreas is the largest gland in the body and is situated transversely across the posterior wall of the abdomen, at the back of the epigastric and left hypochondriac regions.

Its length varies from 12.5-15 cm., and its weight from 60-100 g. It is both an endocrine gland producing several important hormones, including insulin, glucagon, and somatostatin, as well as an exocrine gland, secreting pancreatic juice containing digestive enzymes that pass to the small intestine. These enzymes help in the further breakdown of the carbohydrates, protein, and fat in the chyme.

Pancreatitis is an inflammatory condition of the pancreas which can result in localised and systemic complications.

Localised complications include necrosis and pseudocyst development whereas, systemically, patients can develop systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) and multiple organ failure.

Learning Bite

Patients can develop both localised and systemic complications

Fig1: Detailed pancreas showing Gail Bladder, Common bile duct, Pancreatic duct and duodenum

The pathophysiology of pancreatitis is generally considered in three phases:

Phase 1

Obstruction of bile or pancreatic ducts, or direct toxicity, leads to premature activation of trypsin within pancreatic acinar cells which activates a variety of injurious pancreatic digestive enzymes.

Phase 2

Intrapancreatic inflammation which can lead to necrosis, haemorrhage, infection or the collection of fluid and formation of a pseudocyst

Phase 3

Extrapancreatic inflammation.

Phases 2 and 3 can, in approximately 10-20% of cases, lead to shock and SIRS.

Aetiology and pathogenesis of acute pancreatitis [3]

| Pathogenesis of acute pancreatitis |

Aetiology

|

| Ductal obstruction | Gallstones

Alcohol* Post endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatogpraphy (ERCP) Malignancy Mucinous tumours Pancreas divisum Sphincter of Oddi dysfunction |

| Acinar cell injury | Alcohol*

Trauma Ischaemia Drugs (e.g. Corticosteroids, azathioprine, and thiazides) |

| Defective intracellular transport | Alcohol*

Hereditary Hypercalcaemia Hypertriglyceridaemia Autoimmune |

*Alcohol triggers acute pancreatitis via multiple mechanisms.

History

Most patients experience abdominal pain, typically epigastric with radiation to the back, coupled with persistent nausea, retching and vomiting. Onset of pain is typically sudden, severe and reaches a maximal level quickly. Pain is relieved by nothing and made worse by movement. Fifty percent of patients will have had similar episodes of pain in the past.

Ask about risk factors, such as known gall stone disease, and also significant comorbidities as these can worsen prognosis. Remember that drugs and toxins can cause pancreatitis when taking a drug history. Always ask about alcohol.

Examination

Examination usually reveals a tender upper abdomen which can be combined with guarding; typically the guarding is not as intense as you may expect for the level of pain complained of. This is due to the retroperitoneal location of the pancreas which can make abdominal signs vague.

Jaundice can be present if there is obstruction of the common bile duct in addition to the pancreatic duct.

A paralytic ileus may develop after the first 12-24 hours causing a mild abdominal distension and absent bowel sounds.

Rare and late signs of extensive destruction of the pancreas are bruising around the umbilicus (Cullens sign) or the left flank (Grey Turners sign) due to haemorrhage from the pancreas leading to blood in the abdominal cavity.

Signs of tetany, such as fasciculations, twitching and a positive Trousseaus or Chvosteks test, should also be looked for since hypocalcaemia can develop secondary to intra-abdominal fat necrosis.

Risk Assessment

In 1974, the Ranson criteria was created to predict mortality in acute pancreatitis based upon demographic data and the measurement of several haematological, biochemical, and physiological fields.

Ranson criteria

At admission:

- Age >55

- WCC >16

- Glucose >11

- AST >250

- LDH>350

At 48 hours:

- Calcium <8.0 mg

- Haematocrit fall >10%

- PO2 <60

- Urea increased by 1.8

- Base excess <-4

- Sequestration of fluids >6 L

In the more recent past however, several other severity scores have superseded the original Ranson score.

An international symposium, held in Atlanta in 1992, established a clinically based classification system for predicting acute severe pancreatitis. The criteria and their timings can be seen by selecting the links below. [4]

Initial assessment

APACHE II score >8 is an ICU scoring system based on a variety of parameters; helpful online programs are widely available to aid calculation.

24 hours after admission

Glasgow prognostic criteria (Imries criteria)

The Glasgow system is a simple prognostic system that uses age, and 7 laboratory values collected during the first 48 hours following admission for pancreatitis, to predict severe pancreatitis. It is applicable to both biliary and alcoholic pancreatitis.

A point is assigned if a certain breakpoint is met at any time during that 48-hour period.

The parameters and breakpoints are:

- Age >55 years = 1 point

- Serum albumin <32 g/L (3.2 g/dL) = 1 point

- Arterial PO2 on room air <8 kPa (60 mmHg) = 1 point

- Serum calcium <2 mmols/L (8 mg/dL) = 1 point

- Blood glucose >10.0 mmols/L (180 mg/dL) = 1 point

- Serum LDH >600 units/L = 1 point

- Serum urea nitrogen >16.1 mmols/L (45 mg/dL) = 1 point

- WBC count >15 x 10/L (15 x 10 /microlitre) = 1 point

The addition of the parameter points yields the Glasgow prognostic criteria. The score can range from 0 to 8. If the score is >2, the likelihood of severe pancreatitis is high. If the score is <3, severe pancreatitis is unlikely.

Learning Bite

Any evidence of systemic effects indicates severe pancreatitis and a patient at risk of a poor outcome.

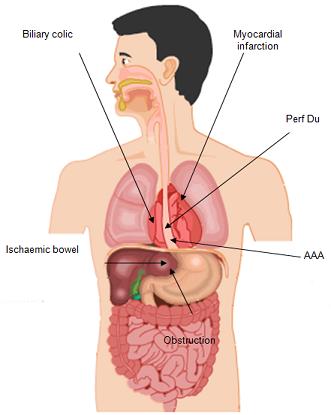

There is wide differential diagnosis which includes any cause of upper abdominal pain or abdominal pain with shock.

Examples are:

- Perforated gastric or duodenal ulcer

- Biliary colic

- Mesenteric ischaemia or infarction

- Dissecting aortic aneurysm

- Intestinal obstruction

- Inferior wall myocardial infarction

Cross section of internal organs and digestive system

Learning Bite

The wide differential diagnosis can make pancreatitis a difficult diagnosis to make clinically.

Aetiology

Everyone is generally taught the mnemonic GET SMASHED, in relation to the causes of acute pancreatitis;

In practice and most research, Gall Stone Disease and Alcohol Consumption account for 75-80% of all cases of acute pancreatitis.

Only a very small number are caused by one of the other causes listed with the remaining number being labelled idiopathic.

The UK Working Party on Acute Pancreatitis states that the aetiology should be established in 80% of cases with no more that 20% labelled as idiopathic [5].

Learning Bite

The majority of cases of acute pancreatitis are caused by gall stones and alcohol.

Investigations should be geared towards diagnosis and prediction of severity.

Thus, immediate assessment should aim for diagnosis of pancreatitis and discovery of any cardiovascular, respiratory or renal compromise. This would include:

1) Urinalysis and pregnancy test in any female of child-bearing age

2) Standard FBC, U&E, LTFs, glucose, CRP

Pancreatic insufficiency may lead to a lack of insulin and subsequent hyperglycaemia and alkaline phosphatase, in particular, may be raised if gall stone obstruction is the cause.

Sometimes used as an early indicator of severity and to monitor progression of inflammation.

- CRP >200 units/L indicates a high risk of developing pancreatic necrosis.

- However, there is ongoing doubt over the diagnostic test accuracy of CRP for predicting pancreatic necrosis. It may take 72 hours after symptom onset to become accurate as an inflammatory marker.

3) Serum calcium

Sequestration of calcium in fat may lead to hypocalcaemia.

4) Serum pancreatic enzymes

Amylase is the most widely used marker of pancreatitis, yet it can be raised in other causes of acute abdominal pain. A normal amylase does not rule out pancreatitis as it can take 24-48 hours to peak, and the degree of elevation of amylase does not equate to severity of disease. Sensitivity is around 80-90% although specificity is as low as 40%. [6,7]

lipase levels remain elevated for longer (up to 14 days after symptom onset vs. 5 days for amylase), providing a higher likelihood of picking up the diagnosis in patients with a delayed presentation.

Although not available at all centres, estimation of plasma lipase shows a slightly superior sensitivity (90%) and specificity (90%) and overall greater accuracy than amylase as it is only produced by the pancreas and has a longer half-life. [6,7]

5) Arterial blood gases

Hypoxia or acidosis may suggest systemic effects.

6) ECG

7) Chest x-ray

Additional tests to determine the aetiology of pancreatitis can be carried out later, e.g. lipid profile, auto-immune antibodies and viral titres.

Further tests for admitted patients are:

- Abdominal ultrasound

- CECT

- MRCP

- EUS

Emerging tests

Urinary trypsinogen-2 (>50 nanograms/mL) shows promise as a diagnostic test.

- Elevated urinary trypsinogen-2 (>50 nanograms/mL) seems to be at least as sensitive and specific as serum lipase and amylase (both at the standard threshold of 3 times the upper limit of normal) for the diagnosis of acute pancreatitis.

- Urinary trypsinogen-2 is a rapid and non-invasive bedside test but is not yet widely available for clinical use.

- A meta-analysis reported a pooled sensitivity of 82% and specificity of 94% for diagnosing acute pancreatitis.

Interleukin-6, interleukin-8, and interleukin-10 may be predictive markers for the development of severe acute pancreatitis.

- One study reported a sensitivity of 81% to 88% and specificity of 75% to 85% for IL-6 and a sensitivity of 65% to 70% and specificity of 69% to 91% for IL-8 for prediction of severe acute pancreatitis.

Learning Bite

Serum lipase is more sensitive and specific than amylase in the diagnosis of pancreatitis, although neither can rule it out.

Treatment for acute pancreatitis is supportive care. Adequate early fluid resuscitation is the single most important aspect in reducing organ failure and in-hospital mortality. The main goal of initial treatment is to provide symptomatic relief and prevent complications which is achieved by reducing pancreatic secretory stimuli and correction of fluid and electrolyte abnormalities. [8]

Patient should be fluid resuscitated and kept nil by mouth with bowel rest when nausea, vomiting or abdominal pain is present. [8]

Initial management plan involves [8]:

- Goal directed rehydration with Ringers lactate/hartmanns solution at rate of 5-10ml/kg/hr

- Optimise analgesia (e.g. Morphine) to prevent diaphragmatic splinting and other respiratory complications

- Oxygen therapy if signs of hypoxia

- Keep NBM

- Antiemetics

- Urinary catheter in severe acute pancreatitis to allow accurate monitoring of fluid balance

- Antibiotics reserved when infection is highly suspected or other concurrent infections suspected

- Involve surgical team and admit ALL patients with suspected pancreatitis.

Emerging treatments

Gastric antisecretory agents

H2 antagonists and proton pump inhibitors may have a role in the treatment of acute pancreatitis by decreasing pancreatic stimulation; however, more research is needed.

CM4620

CM4620, a novel calcium release-activated calcium channel inhibitor for the treatment of acute pancreatitis, has received fast-track designation from the US Food and Drug Administration and orphan designation from the European Medicines Agency. CM4620 is expected to reduce cell damage and death in the pancreas, thereby minimising symptoms.

Learning bite

NICE doesnt currently recommend prophylactic antimicrobials for acute pancreatitis as there is no clear evidence of benefit. [9]

Referral

All patients with suspected or confirmed pancreatitis should be referred promptly to the on-call surgical team once initial assessment has been carried out and appropriate initial management instigated.

Those patients that display features of possible acute severe pancreatitis should be reviewed by senior emergency department staff. They should also be considered early for HDU or ICU care and this should be discussed and arranged with the on-call surgical team.

Patients with organ failure or poor prognostic signs (persistent SIRS, Glasgow score >3, APACHE score >8 and Ranson score >3) should be assessed for admission to a high dependency unit.

Learning Bite

Any patient with haemodynamic instability or features of severe pancreatitis should be managed in a critical care environment.

On-going Management beyond the Emergency Department

Key to Successful Management

The key to the successful management of a patient with pancreatitis is that of good supportive care, with surgery having a very limited role. [7] Accurate fluid management is essential and, in severe cases, this may require invasive monitoring and/or inotropes administered in a critical care area. Patients should be watched for the development of complications and this includes serial clinical assessment, labs and imaging.

Importantly, serial measurements of serum amylase or lipase after diagnosis have limited value in assessing the clinical progress of the illness or prognosis. [10]

Patients with persisting organ failure, signs of sepsis, or deterioration in clinical status after admission will require CT. [7]

Early ERCP is useful in patients with an obstructing gall stone in the common bile duct as the cause, although early cholecystectomy is not warranted. [7]

Surgery and Aetiology

Surgery is really only reserved for selected cases when pancreatitis is complicated by pancreatic or peripancreatic (abdominal fatty tissue) necrosis; the timing of surgery will be dependent on many factors including the patients clinical condition, presence of infection and degree of necrosis, and is largely the surgical teams decision. Minimally invasive step up approach are recommended over open necrosectomy for necrotising pancreatitis, starting with conservative management and then to either percutaneous drainage or endoscopic transluminal drainage.

Patient with gallstone pancreatitis will be considered for cholecystectomy when they are well enough for surgery. If they are surgically unfit or frail, ERCP with biliary sphincterotomy may be considered, but risk should be balanced against risk of recurrent biliary events.

The aetiology of the pancreatitis should be attempted to be determined if it has not already; a diagnosis of idiopathic disease should not be made until a thorough consideration of other causes has been made. This may necessitate revisiting the history, further abdominal USS, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP), endoscopic USS, viral antibody titres, autoimmune markers and ERCP.

Learning Bite

Good supportive care rather than surgery is the mainstay of the management of pancreatitis.

Diagnosis

It should be noted that patients may present with recurrent episodes of acute pancreatitis or they may go on to develop chronic pancreatitis; The distinction between the two should be known.

Recurrent episodes of acute pancreatitis should be self explanatory.

Chronic pancreatitis is used to describe loss of pancreatic function secondary to long term inflammation of the organ. Patients have problems with malabsorption, steatorrhoea, and in some cases the development of diabetes mellitus.

Chronic pancreatitis can present to the emergency department both as acute exacerbations, much like acute pancreatitis, or with a history of chronic pain problems or weight loss/malabsorption. Involvement of the surgical team early in the management of these patients is recommended.

Treatment

Treatment for chronic pancreatitis usually consists of three mainstays; analgesia, oral pancreatic enzyme supplements, and control of blood glucose levels.

The patient may require large amounts of regular opiate medications and also the use of insulin as part of this management.

Surgery for removal of part or all of the pancreas and/or drainage procedures can also be performed in certain cases.

- Pancreatic enzyme levels peak early and decline over 3-4 days, and so a normal amylase cannot rule out pancreatitis.

- Any patient with pancreatitis and haemodynamic instability or risk features should be resuscitated appropriately and referred to critical care.

- Beware the patient with pain worse than clinical findings would suggest think pancreatitis.

- Toh SK, Phillips S, Johnson CD. A prospective audit against national standards of the presentation and management of acute pancreatitis in the South of England. Gut 2000;46:23943.

- Corfield AP, Cooper MJ, Williamson RC. Acute pancreatitis: a lethal disease of increasing incidence. Gut 1985;26:7249.

- Goodchild G, Chouhan M, Johnson GJ. Practical guide to the management of acute pancreatitis. Frontline Gastroenterology. 2019;10:292-299.

- Bradley EL 3rd. A clinically based classification system for acute pancreatitis. Summary of the International Symposium on Acute Pancreatitis, Atlanta, Ga, September 11 through 13, 1992. Arch Surg. 1993 May;128(5):586-90.

- UK Working Party on Acute Pancreatitis. UK guidelines for the management of acute pancreatitis, Gut 2005;54:1-9.

- Tintinalli JE, Ma O, Yealy DM, Meckler GD, Stapczynski J, Cline DM, Thomas SH. eds. Tintinallis Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide, 9e. McGraw-Hill Education; 2020.

- Marx J, Hockberger R, Walls R. Rosens Emergency Medicine Concepts and Clinical Practice, 2-Volume Set. 8th Edition, 2013.

- Goodchild G, Chouhan M, Johnson GJ. Practical guide to the management of acute pancreatitis. Frontline Gastroenterol. 2019 Jul;10(3):292-299.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Pancreatitis -NICE guideline [NG104]. Published: 05 September 2018. Last updated: 16 December 2020.

- Toouli J, Brook-Smith M, Bassi C, et al., Guidelines for the management of acute pancreatitis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2002;(Suppl 17):S1539.

- Jalal M, Campbell JA, Hopper AD. Practical guide to the management of chronic pancreatitis. Frontline Gastroenterology 2019;10:253-260.

- Rompianesi G, Hann A, Komolafe O, et al., Serum amylase and lipase and urinary trypsinogen and amylase for diagnosis of acute pancreatitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 Apr 21;4(4):CD012010.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Pancreatitis acute. NICE CKS, Last revised in May 2021.

- Chang K, Lu W, Zhang K, et al., Rapid urinary trypsinogen-2 test in the early diagnosis of acute pancreatitis: a meta-analysis. Clin Biochem. 2012 Sep;45(13-14):1051-6.