Warning

The content you’re about to read or listen to is at least two years old, which means evidence and guidelines may have changed since it was originally published. This content item won’t be edited but there will be a newer version published if warranted. Check the new publications and curriculum map for updates

Author: Frances Copp / Editor: Liz Herrieven / Codes: / Published: 12/05/2020

Paediatric cases of Bell’s Palsy are relatively uncommon (6.1/100000 in the age range 1-15 (1)); understandably, witnessing a rapidly developing facial asymmetry in a child will cause worried parents/guardians to rush to see a doctor: could their child have had a stroke?? Will it get worse?? Will it be permanent?? After all, not everyone will have come across Sir Charles Bell and his facial nerve experiments, but thanks to the success of the widely broadcast ‘FAST sign’ adverts, many are aware of facial droop as a symptom of a stroke…

Mercifully unlike an acute stroke, the majority of cases will spontaneously resolve with full recovery within 3 months (~70-90%) (2) – most parents may be reassured once you are sufficiently convinced that symptoms are not underpinned by a more sinister pathology. Management strategy is threefold: preventative (eye care), symptom reduction (steroids +/- antivirals) and also with consideration of the psychosocial factors – whilst also true in the adult population, a child of school age could be made particularly vulnerable amongst their peers by anything (however temporary) that makes them appear ‘different’.

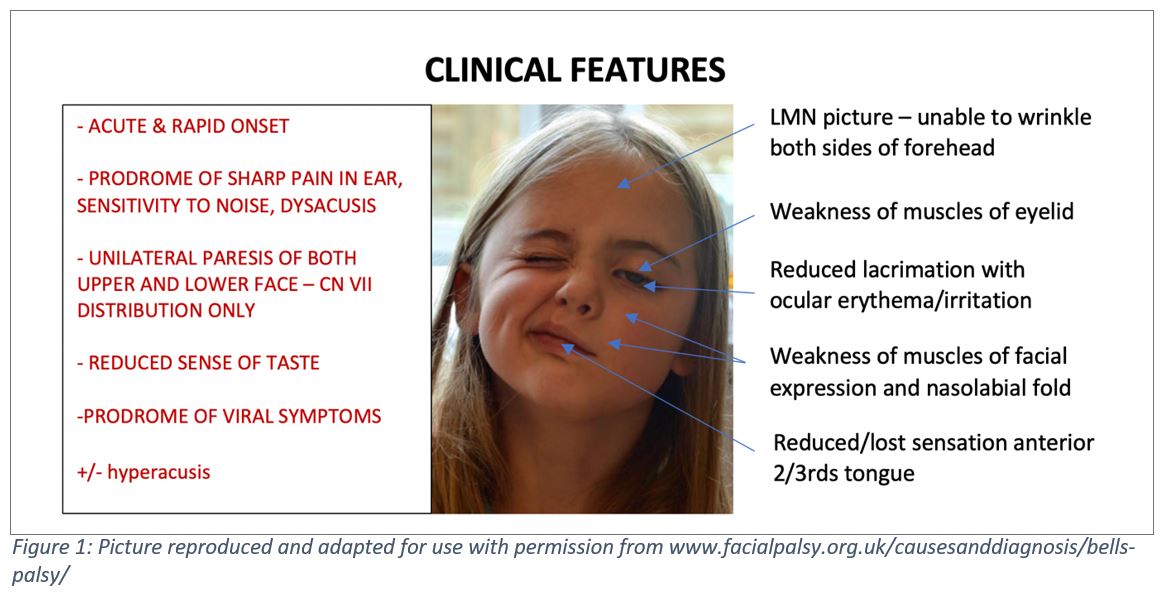

Figure 1: Picture reproduced and adapted for use with permission from www.facialpalsy.org.uk/causesanddiagnosis/bells-palsy/

The Story: what to look for, and what not to miss

Younger children present more of a challenge – especially with more subtle presentations – with heavy reliance on the observational skills of their parents/guardians. The degree of palsy at presentation varies, but even if the clinical signs are not immediately obvious in the consultation room the following may be reported and, if not volunteered, are worth asking about:

– a change in facial expression – asymmetry when smiling/crying/raising eyebrows

– difficulty eating or drinking – with dribbling from the affected side

– increased sensitivity to noise

– tugging ear of affected side/ear pain reported

– recent URTI symptoms

– ‘red eye’ on affected side reduced tear production when crying from affected side, reduced blinking or a ‘lazy lid’

Be aware of the following red flags, which may indicate pathology other than an isolated, idiopathic (or post infective) acute CN VII palsy:

Figure 2: Red flag features

A history of recent viral URTI is common in this age group and for many may have been directly causative – immune response or reactivation of HSV and VZV are thought to be prime causes of otherwise seemingly ‘idiopathic’ palsies in children and adults alike. However, a focussed history can help distinguish between the common ‘just another URTI’ and the weird and sometimes more worrying – see Figure 3 for a non-exhaustive list of differentials. Specifically query risk of Lyme disease (pets, parks, gardens, woodland areas, holidays) and chicken pox history/contact (Ramsay Hunt Syndrome being a key differential). And of the scary, always remember to rule out the possibility of a central neurological cause – any signs or symptoms of a space occupying lesion or additional/ bilateral neurological deficit: be wary – fewer than 1%of all Bell’s palsy cases are bilateral! (4,5)

Neurological assessment: bubbles, toys (and a hard hat!) at the ready!

In addition to the usual Paediatric examination (including exposure hunt the rash!), blood pressure measurement (for HSP/primary hypertensive causes) and a thorough neurological assessment is crucial. For your less co-operative (or simply shy) patients, much of the neurological assessment can be observed from afar: the key is to present yourself as a worthy playmate as early as possible, be as creative as possible and encourage interaction if not with yourself (after all, scrub-syndrome may have already kicked in), with the accompanying adult or any willing siblings. It may be useful to restructure how you approach the examination, simplifying into 4 main groups for ease of observation:

Motor + Co-ordination:

Watching a child under 3 mobilise and handle toys will give an idea of gross strength, co-ordination and limb and truncal tone, and may reveal asymmetry: encourage the child to move (on foot if appropriate and possible) between family members, utilise puzzle toys to observe fine motor skills and co-ordination, or even to reach for and pop bubbles. You should also be able to test a more feisty or reluctant child’s upper and lower limb strength by their ability to wriggle away from you whilst clinging to their familiar adult/sibling (this can also reveal sensation – especially when they pull away whilst refusing to look at you!).

If the child is too young to pull their best faces (puffer-fish face being a winner) for the cranial motor assessment, observation will suffice – especially if encouraged to interact with family. For older children, mutual participation is mandatory: have your most grotesque party face at the ready – occasionally you’ll have to ask parents/siblings to shield eyes from more self-conscious patients, but most children will be keen to show off their best silly face if sufficiently at ease.

Sensation:

If the child is comfortable with you, usually a tickle test will tell all you need to know about sensation this can also be turned into a game (‘shut your eyes no peeping – and tell me which side your teddy is on’- comparing side by side with teddy touch vs light finger touch). If not co-operative, assess the child’s ability to localise and withdraw from your light touch (as mentioned above!) whilst burying their face away from you.

Reflexes:

Be aware that reflexes (particularly the integration of primitive reflexes under the age of 1, although Bell’s palsy in this age group is highly unusual) change through the early years of childhood, and in a younger child the usual ‘adult’ reflexes may not yet be obvious, or may be difficult to elicit. If possible, test the corneal reflex with sterile gauze (stimulating one cornea with light touch should have a consensual blink response, mediated via the ophthalmic branch of the trigeminal [afferent] and temporal/zygomatic branches of the facial nerve [efferent motor]); the affected side may not display a blink reflex when the cornea is stimulated.

Vision:

Pupillary reaction usually can be easily tested but acuity and fields can be more challenging. In the non-co-operative child, observing play with parents covering each eye in turn and encouraging the child to reach for toys can give a basic idea of visual acuity and fields, whilst adapted Snellen charts are available for older children.

In addition to the above, if the child has any eye symptoms, fluorescein drops and blue light to check for any developing corneal injury can be useful, especially if anticipating a call to Ophthalmology services to arrange follow up.

AND NEVER FORGET ENT!!!

Due to the potential for missing a Ramsay Hunt Syndrome (RHS)/raging otitis media if ears and mouth are not examined, ENT examination is especially important. Additionally, be sure to check for any lymphadenopathy or salivary gland swelling/pain.

Figure 6: Mnemonic for VZV Facial palsy

Figure 7: Features of Ramsay Hunt Syndrome. Reproduced from CJ Sweeney, DH Gilden, Ramsay Hunt Syndrome, Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry, 2001; Vol 71, issue 2; 149-154

Investigations?

This is one of the presentations in Paediatrics that may prompt blood tests if any doubt and a long wait to be seen by a doctor, it’s worth getting the magic cream on early. Check your trust guidelines for recommendations (some will advise no investigations if a ‘typical’ presentation), however as a basic approach, consider the following:

– baseline FBC/U&E/CRP

– a blood film (note haematological malignancy as a rare cause of facial palsy)

– Lyme serology, particularly if the history suggests possible exposure to tics.

– If any question of Ramsay Hunt, consider VZV Ab testing.

– Fluorescein drops, whilst technically part of the examination, may be easily forgotten it may help remember them alongside other investigations by using the mnemonic BLUF.

– Although not essential, urinalysis can help to rule out the unusual, although possible, presentation of Bell’s Palsy caused by a vasculitis neuropathy such as Henoch Schonlein Purpura (6)

– If any unusual features, or red flags, imaging (MRI) or more extensive nerve testing may be warranted.

Management

The outcome of this diagnosis can be a little more involved in terms of discharge planning than most other ED presentations: a checklist, therefore, may be useful:

CHECKLIST (essentials in bold)

Management can be split into three categories:

Symptom resolution:

The jury remains out with regard to effective management for those of all ages affected by Bell’s Palsy, with an RCT ongoing in New Zealand looking into management and outcome into the paediatric population alone; most studies suggest possible benefit from corticosteroid therapy, with possible augmentation with an added antiviral, however the results in children have been less conclusive than in the adult patient population. RCTs suggest early corticosteroid therapy (ideally within the first 24hours) and the younger patient (<8years) will have more favourable outcomes. Until further evidence exists, there may be little harm in concomitant coverage with antivirals if no local guideline exists, ‘Uptodate’ may provide assistance as to choice: typical management consists of a 5-7 day course of antiviral (valaciclovir/acyclovir) and 1-2mg/kg prednisolone for 7 days in those over 2 (max 40mg), tapering over a further 7 days (14 day total steroid course). Eye care: Even if the patient presents with relatively good eye closure on the affected side, be aware that things may change over the course of the condition and may worsen before they improve. Therefore, it is always worth teaching the patient and their parents the principals of eye care on presentation: – regular lubrication (dependent on the degree of eye closure if significant, 4 x day Hypromellose ointment, or 1-2 hourly Hypromellose drops should suffice; if eye closure minimally impaired, 4x day Hypromellose drops alone may be sufficient). – If any suspicion of infection (discharge, irritation); or a confirmed corneal abrasion, it is worth also covering with chloramphenicol drops, alongside referral to Ophthalmology for review. – Eye taping overnight helps to protect the eye from further injury; facialpalsy.org.uk have an excellent instruction video, that can assist health care professionals and patients alike:

If eye closure is severely impaired, it is worth considering the use of an eye patch and regular taping with lubricant ointment to prevent foreign body damage. Psychosocial: Whilst in days of old the approach may have been to ‘just get on with it’, the recognition of the rise in mental health difficulties in teenagers and younger children should prompt consideration of any factors that may negatively affect a young person’s mental wellbeing. Unfortunately, an obvious facial palsy with associated features of dribbling/inability to blink (even wearing an eye patch) may cause both the child distress as well as presenting an obvious target for bullying. This is extremely difficult to counteract in the ED setting, especially with a very self-aware teenager, but reassurance that the palsy should resolve with time, and acknowledgment that this may be difficult for the child in terms of self-image can help to validate their reaction and concerns, and can help to raise the issue with parents. Doing so may help open conversation at home; asking the child who they can talk to if they are feeling low can also aid in building a sense of support network particularly if bullying is a particular concern (safe place/safe person etc). Whilst not suitable for all, for the right patient, make-up advice is also available.

For younger children, usually parents will have flagged the issue to the school, and those of pre-school age will not have the worry of the reaction of their peers. Explaining why they look different can be more of a challenge: stories are extremely useful telling the child that their smile has been ‘borrowed’ and that they need to keep practicing so that it may return can help parents address this; if looking for something more physical, there are also books that may help with explanation (see facialpalsy.org).

Follow up

All patients should have a review in ENT clinic within 4-6 weeks of symptom onset; most also advocate GP review (especially for younger children) every 1-2 weeks, to ensure no additional or worsening symptoms. If any worsening features arise, or the palsy is persistent beyond 3 months, the child should be referred to either Paediatric Acute Assessment clinic for further assessment.

Additional referral depends on symptoms: any ocular (corneal) concern refer to Ophthalmology; any unusual symptoms at presentation refer to the Paediatric/Neurology team for review and further assessment.

Parents/Guardians/the patient should be safety netted specifically for features of additional neurological compromise, signs of corneal injury, development of a rash consistent with RHS and advised to return for review if any concerns.

Further RCEM Resources

Full formal Bell’s Palsy in Children learning modules

Acute facial palsy learning module

Facial palsy reference article

CN VII – XII

SAQ

Further Resources

– UK Facial Palsy Charity – info leaflets, videos on eye care, books: ‘when teddy lost his smile’

– Comprehensive guide to management/follow-up

References

- Andrea Ciorba, Virginia Corazzi, et al, ‘Facial nerve paralysis in children’, World Journal of Clinical Cases 2015 Dec 16; 3 (12): 973-979

- Ibid, Marenda SA, Olsson JE. The evaluation of facial paralysis. Otolaryngol Clin North Am1997;30:66982.

- MJ Morrow, ‘Bell’s Palsy and Herpes Zoster Oticus’, Current Treatment Options Neurology, 2000 Sept; 2(5): 407-416

- D. C. Teller and T. P. Murphy, “Bilateral facial paralysis: a case presentation and literature review,” Journal of Otolaryngology, 1992; 21(1):4447

- J. R. Keane, “Bilateral seventh nerve palsy: analysis of 43 cases and review of the literature,” Neurology, 1994; 44(7): 1198-1202

- Nashaat El Sayed Farara et al, Henoch Schonlein Purpura with Facial Palsy’, International Journal of Medical and Pharmaceutical Case Reports, 2015; 3(3): 64-67

- Franz E. Babl et al, ‘Bell’s Palsy in Children (BellPIC): Protocol for a multicentre, placebo controlled randomized trial’, BMC Pediatrics December 2017; 17(1): 53

- E Karatoprak, S Yilmaz ‘Prognostic Factors Associated with Recovery in Children with Bell’s Palsy’, Journal of Child Neurology, Dec 2019; 34 (14): 891-896

- Y Lee, H SooYoon, SG Yeo, EH Lee, ‘Factors Associated with Fast Recovery of Bell’s Palsy in Children’, J Child Neurology 2020; 35 (1): 71-76

FIGURES

- Picture reproduced and adapted for use with permission here

- Red flag features – combined

- Differential diagnosis for facial nerve palsy

- Table taken from House- Brackmann Facial Nerve Grading System, JW House, DU Brackmann, ‘Facial Nerve Grading System’, Otolaryngology, Head and Neck Surgery, 1985; 93:146-7

- Mnemonic for VZV Facial palsy, taken from here

- Features of Ramsay Hunt Syndrome. Reproduced from CJ Sweeney, DH Gilden, ‘Ramsay Hunt Syndrome’, Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry, 2001; Vol 71, issue 2; 149-154

- ‘BLUF’ Mnemonic for Bell’s Palsy investigations: Bloods, Lyme serology, Urinalysis, Fluorescein.

- Management plan checklist